If you were a shark, what would you be?

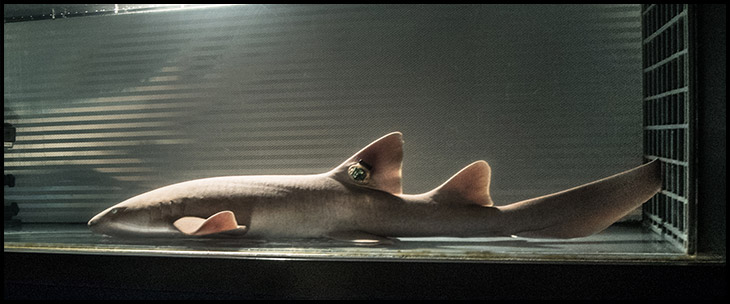

If I was a shark, I would have to be a nurse shark. They are brutally tough, but can be tolerant and almost friendly, always underestimated but never predictable, strong and intelligent, as many studies have shown, and get to hang out on coral reefs eating crabs lobster, shrimp, and conch. How does it get any better than that?!

Could you summarize what you do for research?

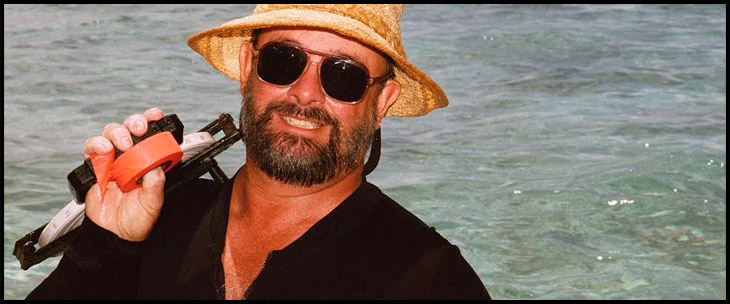

My studies have always focused on the biology of nurse sharks. I first began to study the physiological basis of salt and water balance and then began to focus more on field studies that included growth, aging, and movement studies. The last two decades have been spent studying reproduction and mating behaviors, trying to come to grips with the behaviors that govern mate choice, genetic diversity, and the physiology of reproduction.

What does a typical field day look like?

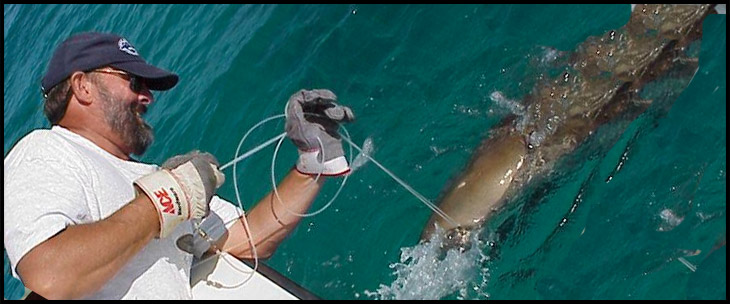

Daytime activities vary considerably. They may be spent setting lines for sharks and then capturing, weighing, measuring, tagging, and releasing subject animals. They may be spent baking in the sun for 10 to 12 hours waiting for a mating event to unfold, and then beginning a frantic ten minutes that may include filming the mating behaviors. In recent years much of my time has been spent writing and editing technical books that cover every aspect of shark biology. In that endeavor I am privileged to work with many of the foremost shark biologists from around the world as they provide their research and experience for book chapters.

What inspired you to start doing this?

My first SCUBA dive when I was a kid brought me into contact with a small shark. I feared for my life, needlessly. So little was known about these mysterious and captivating animals that I simply decided to learn as much as I could. That was fifty years ago. Nothing has changed. I am still mesmerized by these fascinating creatures. And I am still learning.

Why do you think it’s important?

The roles of sharks as apex predators in the aquatic environment is central to the health and survival of oceanic ecosystems. We have ample examples of catastrophic failures in terrestrial systems as consequences of removing top level predators. By the time we begin to see signs of alterations to the health of the planet’s vast marine ecosystems, it may simply be too late for recovery in spite of what may be our best efforts. Sharks have been taken in huge quantities commercially for too many years without having some sense of their natural rates of replenishment. Until we better understand the factors that influence successful reproduction and how large the populations must be to sustain their levels, we cannot hope to preserve sufficient numbers of these animals to insure future population stability.

What is the hardest thing about doing this?

Time. Funding. Patience. It is so difficult to find the time to understand natural processes that are so slow. For example, nurse sharks may not reach sexual maturity for 20 years. If they have young, it would take 20 more years to track them to maturity and reproduction, assuming of course that one could actually follow them through every day and every facet of their life histories. This may vary for other species. But forty years of investment to examine natural mortalities, successful growth to maturity, and eventual reproductive success seems like a long time if a species is at risk for extinction.

What is the most rewarding thing about it?

Being in the water with nine-foot sharks while they are mating, their most intimate moments, and being ‘tolerated’ by the animals is an unimaginable experience. The ‘adrenalin shakes’ take hours to wear off and the experience is simply unmatched by anything else I have ever done.

What if others want to help in shark conservation – how can they help?

Anyone interested in helping protect any species has the obligation to learn everything they can about that species. Being an informed advocate will aid the conservation effort far more than just being a vocal advocate. Evidence and fact are powerful weapons. Be fully armed.

Finally, do you have any advice for a young student wanting to study something like this? What would you tell them?

Be prepared to compete. Many young people see the marine sciences as a glorious profession. It certainly can be, but it will take time, perseverance, the willingness to compete for classes, for admission to graduate schools, for competitive grant funding, for locating jobs, for producing publications, and in virtually every aspect related to your future studies. If this seems discouraging, then you know now that this is not for you! BUT… if you have the ‘right stuff…’