The Burmese Python - A docile(ish) giant

Python bivittatus

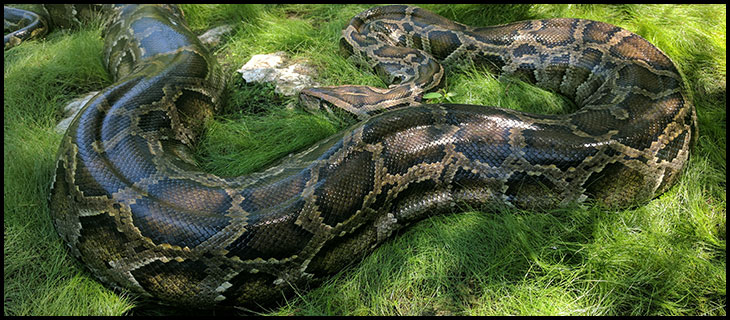

The Burmese Python is one of the largest snakes in the world. It may not hold the record for the longest snake (given to the reticulated python) or the record for the heaviest (a green anaconda holds that), but it is very close in both aspects. Experts generally agree that the snake could approach 23′ long although snakes in the wild over 20′ are extremely rare.

Constricting power of the Burmese Python.

The Burmese python is basically a giant mass of muscle. It is a sit and wait predator that relies on it’s ability to subdue it’s prey via constriction. That means, that unlike vipers that rely on a relatively quick bit of toxic venom, these snakes must squeeze it’s prey to death. One too many owners of these snakes have found out just how deadly these coils can be. Every few years they tend to get out of their cages `

It doesn’t take a large Burmese python to kill a relatively large prey. People for instance, have died from 13′ pythons. They’ve also been both killed and consumed by 23′ pythons (a reticulated python).

What do Burmese Pythons Eat?

Burmese Pythons are opportunistic ambush predators that can consume prey from as little as about 5% of their body size to close to 50% of their body size. This means that the prey of a Burmese python will change throughout it’s life. Small individuals will feed on small mammals such as mice, rats and other similarly sized fur-bearing animals. They also feed on birds, both domestic and wild. As their size increases they may feed on larger prey, like pigs and goats. Burmese python that have invaded the everglades have been recorded preying on alligators and even adult deer.

In Florida, the invasive Burmese pythons have be shown to have the following species in their guts: Rabbit (Sylvilagus sp.) Hispid cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus) Cotton mouse (Peromyscus gossypinus) Gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) Fox squirrel (Sciurus niger) Domestic cat (Felis catus) Raccoon (Procyon lotor) Old world rats (Rattus sp.) Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana) Bobcat (Felis rufus) Round-tailed muskrat (Neofiber alleni) Rice rat (Oryzomys palustris) White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) Key Largo woodrat (Neotoma floridana smalli) Birds include the Pied-billed grebe (Podilymbus podiceps) Limpkin (Aramus guarauna) White ibis (Eudocimus albus) American coot (Fulica american) House wren (Troglodytes aedon) Reptiles American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis)

Python’s ability to digest large prey

Like deep sea fish whom consume extremely large prey relative to their body size, the Burmese python has an amazing ability to consume very large prey. It could easily digest something that was 50% the mass of the snake. To put that in relative terms, imagine a 200 pound human consuming a small 100 pound individual in one sitting. The thought is mind-blowing if you think about it. For these snakes though, it’s a common occurrence. To do this it must have a few special adaptations.

Python Jaws

First, it must physically get the prey into it’s mouth. This may be the biggest limiter. Often the shoulder blades on mammals are what limit the snake in it’s search for food. Unlike our jaws though, their mouth will open up to 150 degrees. The bottom jaw (lower mandibles) are also not connected in the front. Look at this photo of this python skull. Notice the separated lower jaws.

The size of the stomach

Oddly, these pythons do not need to get the entire prey item into their stomach to consume it. Instead, the stomach can start digesting part of the prey. Over time, the prey will move further into the stomach. The stomach may be as much as 1/4 the length of the python though. A 20′ snake for instance might be able to fit a 5′ prey item completely inside it.

Digestive Response of Burmese Pythons

The response of a Burmese python to a large prey is truly remarkable. In fact, it has become a model species for studying digestion. Leading the way is Dr. Steven Secor at the University of Alabama. He has been feeding Burmese pythons different types of prey and then trying to figure out what happens inside them. What he and his students have found is unlike anything we’re used to in humans.

Humans for instance, have fasting stomachs that are highly acidic. As food is consumed however, our stomachs are buffered and become less acidic. These snakes however, have a reduced acidity during fasting. As food is consumed, their stomachs change. The acidity and volume increase. Their intestines increase in size and the mass of the ventricle of the heart increases in size.

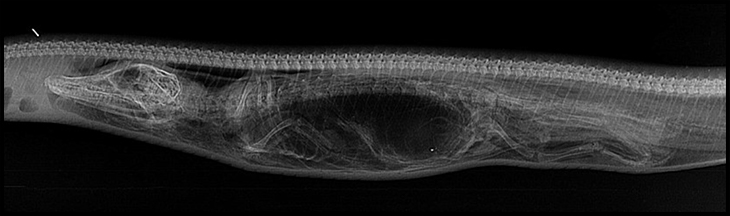

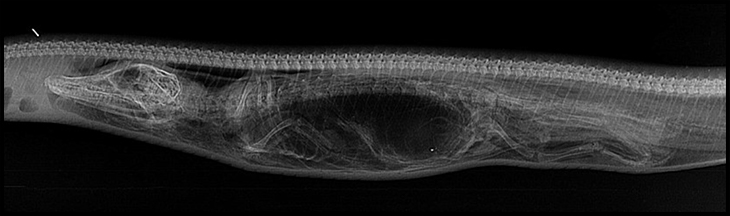

But how fast does a Burmese Python consume it’s prey you might ask? While this differs a bit in the size of their prey, the size of the snake, the type of prey, and the temperature of their surroundings, it is useful to look at the sequential slides of a Burmese python consuming an alligator.

What you’ll notice on day 1 is a fully intact skeleton of the alligator. All the major bones are present. By day 2, some bits of the jaw are starting to dissolve, but it’s still relatively intact. Day 3 and 4 show a great deal of dissolution. By day 5, there are only a few small bones left and by day 6, the alligator is completely consumed.

The only bits of most animals that are hard to digest by these pythons are those bits that contain keratin. Thus, finger nails, hair, claws and some antler-type material may come out in the feces. These serve as the only evidence of the prey item. This fact has made it next to impossible to find evidence of python attacks in the fossil record.

Where does the Burmese Python Live?

The Burmese python is native to south-east Asia from eastern India into Indonesia. It was previously listed as the same species as the Indian python (a very close relative). In many parts of their range they are threatened and fairly well. The Burmese python also lives outside of it’s range as an invasive species in south Florida, particularly in the everglades.

The Invasion in the Everglades

Ever since these snakes have been kept as pets, they have been released by their owners into the wild. A small burmese python will quickly outgrow a small cage and can often become a problem for the owners. Even though good homes could be found for these large individuals, people have a tendency to release some of them back into the wild (a practice that is both foolish and dangerous). However, this was likely not how the everglades got it’s problem burmese pythons.

In 1992, Hurricane Andrew devastated south Florida. The eye of the storm went right over Homestead, a small town just south of Miami. Here, a breeder’s facility was completely demolished and his snakes escaped into the wild. According to some estimates, it was just under 1000 individuals. This became ground zero for the invasion of the everglades.

This initial population didn’t seem to do anything though. It wasn’t until 2000 when the first problematic burmese pythons were discovered. The problem has grown. The government has taken different approaches to control the invasion. In some years they have had an open season on them – a collect as many as you can if you will. They’ve tried tracking males to breeding spots. They’ve tried tagging and baiting. Nothing seems to be a surefire way to get rid of them. They may be here to stay.

In 2017, the South Florida Water Management District decided they were going to have a bounty for these snakes. They hired 25 hunters at 8.25/hr to look for snakes. They were able to get an extra 25 dollars for every foot of the snake they brought in. These hunters however, are still not able to find too many. When we went out with them, they only had a couple of weeks left in the season and had only caught about 80 snakes.

What this means for south florida is unclear. We know that these are large apex predators, similar in the food pyramid to where the alligator stands. They likely will not replace the alligators, but merely become yet another predator in the system that organisms in the glades will have to deal with. Right now it seems that it is next to impossible to get them all out.

Related Topics

The Burmese Python is one of the largest snakes in the world. It may not hold the record for the longest snake (given to the reticulated python) or the record for the heaviest (a green anaconda holds that), but it is very close in both aspects. Experts generally agree that the snake could approach 23′ long although snakes in the wild over 20′ are extremely rare.

Constricting power of the Burmese Python.

The Burmese python is basically a giant mass of muscle. It is a sit and wait predator that relies on it’s ability to subdue it’s prey via constriction. That means, that unlike vipers that rely on a relatively quick bit of toxic venom, these snakes must squeeze it’s prey to death. One too many owners of these snakes have found out just how deadly these coils can be. Every few years they tend to get out of their cages `

It doesn’t take a large Burmese python to kill a relatively large prey. People for instance, have died from 13′ pythons. They’ve also been both killed and consumed by 23′ pythons (a reticulated python).

What do Burmese Pythons Eat?

Burmese Pythons are opportunistic ambush predators that can consume prey from as little as about 5% of their body size to close to 50% of their body size. This means that the prey of a Burmese python will change throughout it’s life. Small individuals will feed on small mammals such as mice, rats and other similarly sized fur-bearing animals. They also feed on birds, both domestic and wild. As their size increases they may feed on larger prey, like pigs and goats. Burmese python that have invaded the everglades have been recorded preying on alligators and even adult deer.

In Florida, the invasive Burmese pythons have be shown to have the following species in their guts: Rabbit (Sylvilagus sp.) Hispid cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus) Cotton mouse (Peromyscus gossypinus) Gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) Fox squirrel (Sciurus niger) Domestic cat (Felis catus) Raccoon (Procyon lotor) Old world rats (Rattus sp.) Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana) Bobcat (Felis rufus) Round-tailed muskrat (Neofiber alleni) Rice rat (Oryzomys palustris) White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) Key Largo woodrat (Neotoma floridana smalli) Birds include the Pied-billed grebe (Podilymbus podiceps) Limpkin (Aramus guarauna) White ibis (Eudocimus albus) American coot (Fulica american) House wren (Troglodytes aedon) Reptiles American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis)

Python’s ability to digest large prey

Like deep sea fish whom consume extremely large prey relative to their body size, the Burmese python has an amazing ability to consume very large prey. It could easily digest something that was 50% the mass of the snake. To put that in relative terms, imagine a 200 pound human consuming a small 100 pound individual in one sitting. The thought is mind-blowing if you think about it. For these snakes though, it’s a common occurrence. To do this it must have a few special adaptations.

Python Jaws

First, it must physically get the prey into it’s mouth. This may be the biggest limiter. Often the shoulder blades on mammals are what limit the snake in it’s search for food. Unlike our jaws though, their mouth will open up to 150 degrees. The bottom jaw (lower mandibles) are also not connected in the front. Look at this photo of this python skull. Notice the separated lower jaws.

The size of the stomach

Oddly, these pythons do not need to get the entire prey item into their stomach to consume it. Instead, the stomach can start digesting part of the prey. Over time, the prey will move further into the stomach. The stomach may be as much as 1/4 the length of the python though. A 20′ snake for instance might be able to fit a 5′ prey item completely inside it.

Digestive Response of Burmese Pythons

The response of a Burmese python to a large prey is truly remarkable. In fact, it has become a model species for studying digestion. Leading the way is Dr. Steven Secor at the University of Alabama. He has been feeding Burmese pythons different types of prey and then trying to figure out what happens inside them. What he and his students have found is unlike anything we’re used to in humans.

Humans for instance, have fasting stomachs that are highly acidic. As food is consumed however, our stomachs are buffered and become less acidic. These snakes however, have a reduced acidity during fasting. As food is consumed, their stomachs change. The acidity and volume increase. Their intestines increase in size and the mass of the ventricle of the heart increases in size.

But how fast does a Burmese Python consume it’s prey you might ask? While this differs a bit in the size of their prey, the size of the snake, the type of prey, and the temperature of their surroundings, it is useful to look at the sequential slides of a Burmese python consuming an alligator.

What you’ll notice on day 1 is a fully intact skeleton of the alligator. All the major bones are present. By day 2, some bits of the jaw are starting to dissolve, but it’s still relatively intact. Day 3 and 4 show a great deal of dissolution. By day 5, there are only a few small bones left and by day 6, the alligator is completely consumed.

The only bits of most animals that are hard to digest by these pythons are those bits that contain keratin. Thus, finger nails, hair, claws and some antler-type material may come out in the feces. These serve as the only evidence of the prey item. This fact has made it next to impossible to find evidence of python attacks in the fossil record.

Where does the Burmese Python Live?

The Burmese python is native to south-east Asia from eastern India into Indonesia. It was previously listed as the same species as the Indian python (a very close relative). In many parts of their range they are threatened and fairly well. The Burmese python also lives outside of it’s range as an invasive species in south Florida, particularly in the everglades.

The Invasion in the Everglades

Ever since these snakes have been kept as pets, they have been released by their owners into the wild. A small burmese python will quickly outgrow a small cage and can often become a problem for the owners. Even though good homes could be found for these large individuals, people have a tendency to release some of them back into the wild (a practice that is both foolish and dangerous). However, this was likely not how the everglades got it’s problem burmese pythons.

In 1992, Hurricane Andrew devastated south Florida. The eye of the storm went right over Homestead, a small town just south of Miami. Here, a breeder’s facility was completely demolished and his snakes escaped into the wild. According to some estimates, it was just under 1000 individuals. This became ground zero for the invasion of the everglades.

This initial population didn’t seem to do anything though. It wasn’t until 2000 when the first problematic burmese pythons were discovered. The problem has grown. The government has taken different approaches to control the invasion. In some years they have had an open season on them – a collect as many as you can if you will. They’ve tried tracking males to breeding spots. They’ve tried tagging and baiting. Nothing seems to be a surefire way to get rid of them. They may be here to stay.

In 2017, the South Florida Water Management District decided they were going to have a bounty for these snakes. They hired 25 hunters at 8.25/hr to look for snakes. They were able to get an extra 25 dollars for every foot of the snake they brought in. These hunters however, are still not able to find too many. When we went out with them, they only had a couple of weeks left in the season and had only caught about 80 snakes.

What this means for south florida is unclear. We know that these are large apex predators, similar in the food pyramid to where the alligator stands. They likely will not replace the alligators, but merely become yet another predator in the system that organisms in the glades will have to deal with. Right now it seems that it is next to impossible to get them all out.