Mako Sharks: The Speeding Bullets of the Ocean

Isurus oxyrinches

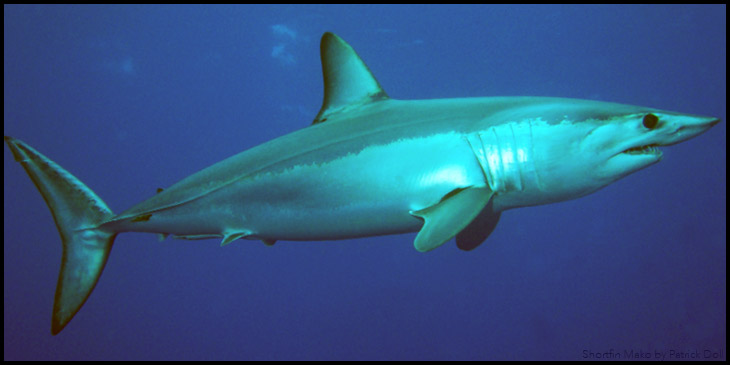

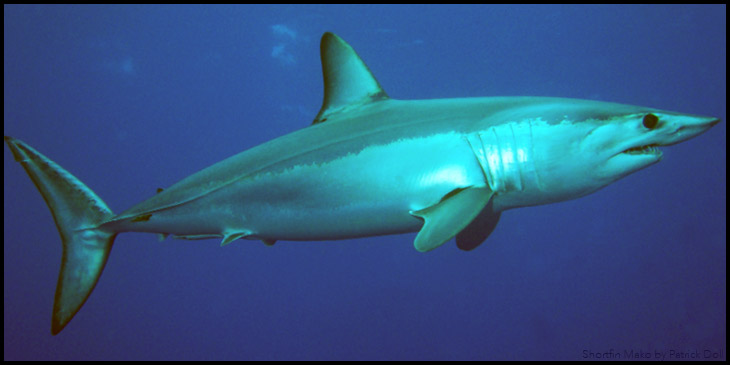

Imagine if you set out to create the leanest, meanest, fastest predatory shark the ocean ever saw. You might start out with a smooth, thin, torpedo-shaped body and add in some super-strong muscles attached to a powerful tail. To top it off, add a pointy snout that can cut through the water like glass.

Congratulations, my friend, you’ve just designed a mako shark. These crazy animals are the fastest known sharks in existence, clocking in at a record-shattering 60 miles per hour. That’s not the only cool thing about them, though—read on for more!

What is a mako shark?

Mako sharks are another nondescript gray shark. They don’t have any fancy skin patterns, but what they lack in decoration they make up for with a missile-shaped body, usually between 7-12 feet in length. They have large teeth—so big, in fact, that they still stick out when the shark closes its mouth!

Mako sharks come in two flavors: the shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus) and the longfin mako (Isurus paucus). Shortfin makos are by far the most common species.

It’s unlikely you’ll run into the longfin mako, but if you do, consider yourself lucky. Scientists still don’t know a lot about this particular shark species yet. It’s thought that they live deep in the ocean, which might explain why shark scientists (with their boats on the surface) can’t get to them easily to study.

Mako shark biology turns it into a speed machine.

Mako sharks have a lot of biological features besides the shape of their body that make them shark speed champions. They possess two sets of muscles running down the sides of their body that act just like pistons in moving their tails back and forth. You can see how fast and agile they are in this video:

These powerful muscles also take advantage of countercurrent heat exchangers, a unique feature also found in species like salmon sharks and porbeagles. These are a unique way of lining up blood vessels going to and from the cold parts of the body (like fins) next to blood vessels coming from warm parts of the body (like the heart).

By lining up these two sets of blood vessels—cold with warm—the shark can retain heat from its own body so that its muscles get a warm boost. Warm muscles translate into more efficient muscles, so the shark can move even faster! In fact, the mako is one of the only shark species in the world that is warm-blooded, thanks to its countercurrent heat exchangers.

Where do mako sharks live?

Imagine a band centered around the world on the equator. That’s mako territory. They prefer living in the pelagic biome (i.e., the open ocean), so it’s not likely you’ll run into these guys unless you’re far away from shore.

Mako sharks like to move around—a lot. Some mako sharks have been recorded bouncing around the ocean more times than a pinball.

How are mako shark populations doing?

Both the shortfin mako and the longfin mako are classified as vulnerable according to the IUCN. That means that as a whole, mako sharks are just one step away from being endangered.

Just like with their porbeagle cousins, mako sharks are a popular fishing target. They have excellent meat, and those acrobatic maneuvers they can carry out underwater means they put up one heck of a fight.

Members of United Nations countries have agreed on certain regulations governing mako sharks under the 1995 Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks Agreement (UNFSA; say that ten times fast), however most countries aren’t abiding by these rules yet. Rather, mako shark conservation regulations are a bit piecemeal depending on what country you’re in (or near).

Because mako sharks tend to migrate so much, it’s hard to keep tabs on their population in any one area and apply a consistent set of rules. For example, what happens if a shark in Brazil decides to go on a sunset cruise to the United States, where a whole different set of regulations apply? Unfortunately, mako sharks don’t stay within the boundary waters of the countries they’re born in.

There are a lot of other compounding factors causing mako shark populations to be so low, and one of them is bad scientific data.

It’s important for scientists to know the age of sharks so they can put this information into models that generate sustainable harvest rates. Scientists used to think that mako sharks put down two growth rings per year in the vertebrae they use to age the sharks. However, they recently discovered that they actually put down one growth ring per year, just like normal sharks. This means that a shark with 30 growth rings is not 15 years old; it’s actually 30 years old. All the mako sharks scientists have aged are actually twice as old as we thought! This means the models were giving inaccurate data that’s potentially harmful to the population.

Luckily, mako sharks do have a pretty high ability to recover from low population sizes. Female mako sharks can give birth to anywhere from 10-18 pups every three years—that’s quite a lot of little sharks! Now we just need better, more consistent regulations across the different countries to allow the sharks to take advantage of this inherent capacity to grow fast, and then we won’t need to worry about having low mako shark populations anymore.

Related Topics

Imagine if you set out to create the leanest, meanest, fastest predatory shark the ocean ever saw. You might start out with a smooth, thin, torpedo-shaped body and add in some super-strong muscles attached to a powerful tail. To top it off, add a pointy snout that can cut through the water like glass.

Congratulations, my friend, you’ve just designed a mako shark. These crazy animals are the fastest known sharks in existence, clocking in at a record-shattering 60 miles per hour. That’s not the only cool thing about them, though—read on for more!

What is a mako shark?

Mako sharks are another nondescript gray shark. They don’t have any fancy skin patterns, but what they lack in decoration they make up for with a missile-shaped body, usually between 7-12 feet in length. They have large teeth—so big, in fact, that they still stick out when the shark closes its mouth!

Mako sharks come in two flavors: the shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus) and the longfin mako (Isurus paucus). Shortfin makos are by far the most common species.

It’s unlikely you’ll run into the longfin mako, but if you do, consider yourself lucky. Scientists still don’t know a lot about this particular shark species yet. It’s thought that they live deep in the ocean, which might explain why shark scientists (with their boats on the surface) can’t get to them easily to study.

Mako shark biology turns it into a speed machine.

Mako sharks have a lot of biological features besides the shape of their body that make them shark speed champions. They possess two sets of muscles running down the sides of their body that act just like pistons in moving their tails back and forth. You can see how fast and agile they are in this video:

These powerful muscles also take advantage of countercurrent heat exchangers, a unique feature also found in species like salmon sharks and porbeagles. These are a unique way of lining up blood vessels going to and from the cold parts of the body (like fins) next to blood vessels coming from warm parts of the body (like the heart).

By lining up these two sets of blood vessels—cold with warm—the shark can retain heat from its own body so that its muscles get a warm boost. Warm muscles translate into more efficient muscles, so the shark can move even faster! In fact, the mako is one of the only shark species in the world that is warm-blooded, thanks to its countercurrent heat exchangers.

Where do mako sharks live?

Imagine a band centered around the world on the equator. That’s mako territory. They prefer living in the pelagic biome (i.e., the open ocean), so it’s not likely you’ll run into these guys unless you’re far away from shore.

Mako sharks like to move around—a lot. Some mako sharks have been recorded bouncing around the ocean more times than a pinball.

How are mako shark populations doing?

Both the shortfin mako and the longfin mako are classified as vulnerable according to the IUCN. That means that as a whole, mako sharks are just one step away from being endangered.

Just like with their porbeagle cousins, mako sharks are a popular fishing target. They have excellent meat, and those acrobatic maneuvers they can carry out underwater means they put up one heck of a fight.

Members of United Nations countries have agreed on certain regulations governing mako sharks under the 1995 Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks Agreement (UNFSA; say that ten times fast), however most countries aren’t abiding by these rules yet. Rather, mako shark conservation regulations are a bit piecemeal depending on what country you’re in (or near).

Because mako sharks tend to migrate so much, it’s hard to keep tabs on their population in any one area and apply a consistent set of rules. For example, what happens if a shark in Brazil decides to go on a sunset cruise to the United States, where a whole different set of regulations apply? Unfortunately, mako sharks don’t stay within the boundary waters of the countries they’re born in.

There are a lot of other compounding factors causing mako shark populations to be so low, and one of them is bad scientific data.

It’s important for scientists to know the age of sharks so they can put this information into models that generate sustainable harvest rates. Scientists used to think that mako sharks put down two growth rings per year in the vertebrae they use to age the sharks. However, they recently discovered that they actually put down one growth ring per year, just like normal sharks. This means that a shark with 30 growth rings is not 15 years old; it’s actually 30 years old. All the mako sharks scientists have aged are actually twice as old as we thought! This means the models were giving inaccurate data that’s potentially harmful to the population.

Luckily, mako sharks do have a pretty high ability to recover from low population sizes. Female mako sharks can give birth to anywhere from 10-18 pups every three years—that’s quite a lot of little sharks! Now we just need better, more consistent regulations across the different countries to allow the sharks to take advantage of this inherent capacity to grow fast, and then we won’t need to worry about having low mako shark populations anymore.