Learn to Love Lichens

Lichen Diversity

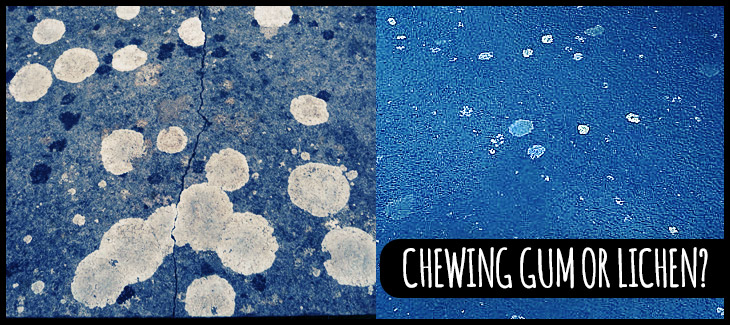

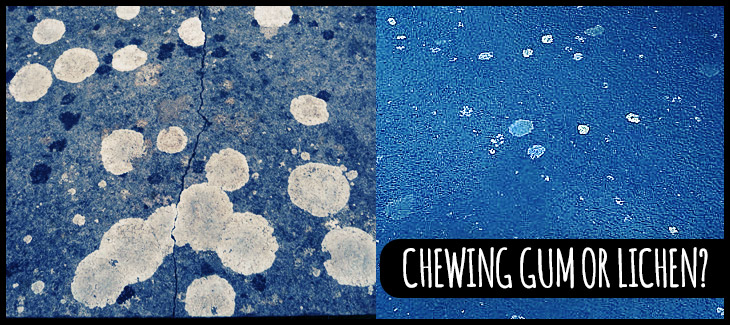

A smear of gum will cling to a park bench as if its life (if it had one) depended on it, a little bit like a lichen. Also like lichens, gum smears appear as pastel-colored scabs, which passers-by rarely ever notice, let alone stop to ponder. It’s a sad truth that lichens don’t receive a negative wrap; much worse, they get no wrap at all. They are the unsung heroes of the plant and fungi worlds, and frankly it is hard to see why.

Before we continue let’s set one thing straight; not all lichens are flat like scabs. In fact 2D, crust-like lichens, sensibly known by lichenologists as crustose lichens, make up just a smallish proportion of the more than 20,000 lichen species known. Most other lichens are fruticose (shrubby, bushy or beard-like in structure) or foliose (lobed or leafy-looking) while others still are something in between. Lichens also come in a huge range of colors, including showy yellows and oranges and reds.

Lichens are Composite Organisms

Yes, as ridiculous as it sounds, a lichen isn’t a single organism but contains at least two different kinds of life. Just like many corals—which consist of colonies of tiny animals that have even tinier plants living inside them—every lichen is made up of organisms belonging to different kingdoms; usually a fungus and a plant, or a fungus and a cyanobacteria (a type of bacteria that can photosynthesize). And these very different sorts of organism have found clever, win-win ways to co-exist.

Why Living Together Works for a Lichen’s Components

Within a lichen, the fungus scores some of the sugary food that the plant or cyanobacteria uses sunshine to produce. Meanwhile the plant/cyanobacteria gets a fungus-walled home in which to stay safe and moist, plus nutrients scrounged by the fungus from the surface it’s stuck to. In rarer cases, seemingly greedy ‘lichenized’ fungi receive food from two different photosynthesising sugar daddies. Lichens, whatever their make-up, represent share-housing at its very best.

The Benefits of Being Composite

Basic lichen biology is an absolute head-spin, so take your time in understanding all of this. Know as well that there is a crazy amount of sense in the lichen’s very weird way of life. Because of it many lichens can survive, and indeed thrive, in places where independent plants and fungi fear to tread. They can grow on surfaces ranging from soil, rock, wood and bone to concrete and metal and glass, and they inhabit every non-icy, non-aquatic (and non sand-dune) environment on Earth.

Add to these talents the value of lichens as colonizers of barren surfaces, absorbers of pollutants, winter food for animals like caribou and reindeer, and sources of color for human clothing, and you can see why lichens deserve much more credit than they get. Learning to love lichens means embracing these unassuming fungus-plant/bacterium pairs much like they embrace signposts and pavements.

Related Topics

A smear of gum will cling to a park bench as if its life (if it had one) depended on it, a little bit like a lichen. Also like lichens, gum smears appear as pastel-colored scabs, which passers-by rarely ever notice, let alone stop to ponder. It’s a sad truth that lichens don’t receive a negative wrap; much worse, they get no wrap at all. They are the unsung heroes of the plant and fungi worlds, and frankly it is hard to see why.

Before we continue let’s set one thing straight; not all lichens are flat like scabs. In fact 2D, crust-like lichens, sensibly known by lichenologists as crustose lichens, make up just a smallish proportion of the more than 20,000 lichen species known. Most other lichens are fruticose (shrubby, bushy or beard-like in structure) or foliose (lobed or leafy-looking) while others still are something in between. Lichens also come in a huge range of colors, including showy yellows and oranges and reds.

Lichens are Composite Organisms

Yes, as ridiculous as it sounds, a lichen isn’t a single organism but contains at least two different kinds of life. Just like many corals—which consist of colonies of tiny animals that have even tinier plants living inside them—every lichen is made up of organisms belonging to different kingdoms; usually a fungus and a plant, or a fungus and a cyanobacteria (a type of bacteria that can photosynthesize). And these very different sorts of organism have found clever, win-win ways to co-exist.

Why Living Together Works for a Lichen’s Components

Within a lichen, the fungus scores some of the sugary food that the plant or cyanobacteria uses sunshine to produce. Meanwhile the plant/cyanobacteria gets a fungus-walled home in which to stay safe and moist, plus nutrients scrounged by the fungus from the surface it’s stuck to. In rarer cases, seemingly greedy ‘lichenized’ fungi receive food from two different photosynthesising sugar daddies. Lichens, whatever their make-up, represent share-housing at its very best.

The Benefits of Being Composite

Basic lichen biology is an absolute head-spin, so take your time in understanding all of this. Know as well that there is a crazy amount of sense in the lichen’s very weird way of life. Because of it many lichens can survive, and indeed thrive, in places where independent plants and fungi fear to tread. They can grow on surfaces ranging from soil, rock, wood and bone to concrete and metal and glass, and they inhabit every non-icy, non-aquatic (and non sand-dune) environment on Earth.

Add to these talents the value of lichens as colonizers of barren surfaces, absorbers of pollutants, winter food for animals like caribou and reindeer, and sources of color for human clothing, and you can see why lichens deserve much more credit than they get. Learning to love lichens means embracing these unassuming fungus-plant/bacterium pairs much like they embrace signposts and pavements.