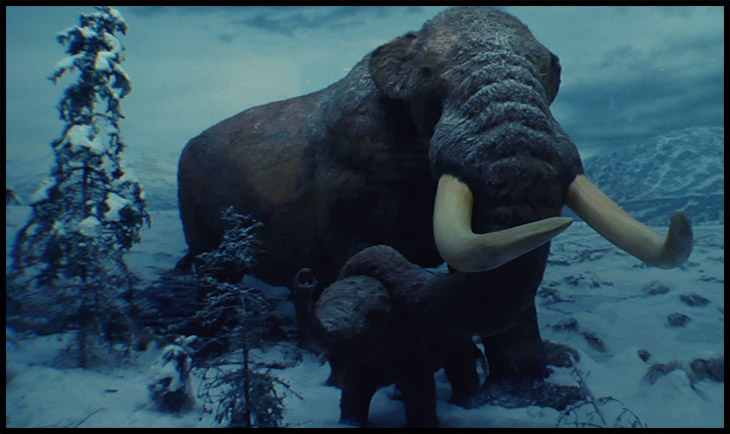

Bringing Back the Woolly Mammoth

Mammuthus primigenius

Extincting the woolly mammoth wasn’t easy, let’s make no bones about that. It took a lot of labor-intensive spear-crafting and man vs. beast showdowns in the snow, plus a pinch of climate change, to push this megafauna species into oblivion. But de-extincting the mammoth? Well, that’s arguably even more of a mega-challenge for humankind. One that we are nevertheless creeping towards conquering.

“We” in this instance is a team of scientists at Harvard University, whose work involves applying modern genetic engineering techniques to prehistoric mammoth DNA. To date, 39 mammoth bodies have been extracted from sites across Eurasia and North America, where mammoths roamed until about 3,600 years ago. By tinkering with genetic material from these remains the researchers have had some big wins.

Woolly Mammoth Revival: The Progress Report

The Harvard team has already successfully spliced woolly mammoth genes into live Asian elephant cells grown in the lab, a task that’s no doubt even more finicky than it sounds. Next on the researchers’ list of things to do is turn these “blank” hybrid cells into specialized cells—including red blood cells, fat cells and ear cells—so they can study the traits that result from expression of the mammoth genes they contain.

Key Woolly Mammoth Adaptations

Despite how it may seem, the blood, fat and ears of mammoths weren’t selected for special investigation at random. The ability of mammoth red blood cells to release more oxygen in cold temperatures, the tendency of mammoth fat cells to form a blubbery layer under the skin, and the relatively small size of mammoth ears were all adaptations that helped these massive mammals dominate in chilly environments, unlike their elephant cousins, who strictly preferred warmer climes.

Introducing the “Elemoth” or “Mammephant”

These days, elephants still don’t mix well with low temperatures, and that’s not expected to change. At least not until they are “reprogrammed” with mammoth genes to do so. See where all this is going? Yes, the Harvard team hopes to engineer elephants able to thrive in the same cold, vast ecosystems as mammoths did, thus improving our ability to conserve elephant species while also reducing greenhouse gas emissions from these areas (it’s a grassland restoration/permafrost insulation thing).

So, technically speaking, we’re on the way to bringing back bits of extinct woolly mammoths rather than these hairy beasts in their entirety. Still, even partially de-extincting a megafauna species is far from easy, as those amongst us who have swapped skills in spear making for those in gene splicing already know very well.

Related Topics

Extincting the woolly mammoth wasn’t easy, let’s make no bones about that. It took a lot of labor-intensive spear-crafting and man vs. beast showdowns in the snow, plus a pinch of climate change, to push this megafauna species into oblivion. But de-extincting the mammoth? Well, that’s arguably even more of a mega-challenge for humankind. One that we are nevertheless creeping towards conquering.

“We” in this instance is a team of scientists at Harvard University, whose work involves applying modern genetic engineering techniques to prehistoric mammoth DNA. To date, 39 mammoth bodies have been extracted from sites across Eurasia and North America, where mammoths roamed until about 3,600 years ago. By tinkering with genetic material from these remains the researchers have had some big wins.

Woolly Mammoth Revival: The Progress Report

The Harvard team has already successfully spliced woolly mammoth genes into live Asian elephant cells grown in the lab, a task that’s no doubt even more finicky than it sounds. Next on the researchers’ list of things to do is turn these “blank” hybrid cells into specialized cells—including red blood cells, fat cells and ear cells—so they can study the traits that result from expression of the mammoth genes they contain.

Key Woolly Mammoth Adaptations

Despite how it may seem, the blood, fat and ears of mammoths weren’t selected for special investigation at random. The ability of mammoth red blood cells to release more oxygen in cold temperatures, the tendency of mammoth fat cells to form a blubbery layer under the skin, and the relatively small size of mammoth ears were all adaptations that helped these massive mammals dominate in chilly environments, unlike their elephant cousins, who strictly preferred warmer climes.

Introducing the “Elemoth” or “Mammephant”

These days, elephants still don’t mix well with low temperatures, and that’s not expected to change. At least not until they are “reprogrammed” with mammoth genes to do so. See where all this is going? Yes, the Harvard team hopes to engineer elephants able to thrive in the same cold, vast ecosystems as mammoths did, thus improving our ability to conserve elephant species while also reducing greenhouse gas emissions from these areas (it’s a grassland restoration/permafrost insulation thing).

So, technically speaking, we’re on the way to bringing back bits of extinct woolly mammoths rather than these hairy beasts in their entirety. Still, even partially de-extincting a megafauna species is far from easy, as those amongst us who have swapped skills in spear making for those in gene splicing already know very well.