Science of the Bushcraft Knife

I often get asked, what is the best survival knife or bushcraft knife. I find it hard to answer because knives are so diverse and the uses of each are unique to the individual using them. I have however, found that there are a few features that everyone should be aware of before they make up their minds. To help me start this discussion I made this short video about it:

I’m going to walk through the basics of a good outdoor knife, all the stuff you might wonder when you’re starting out.

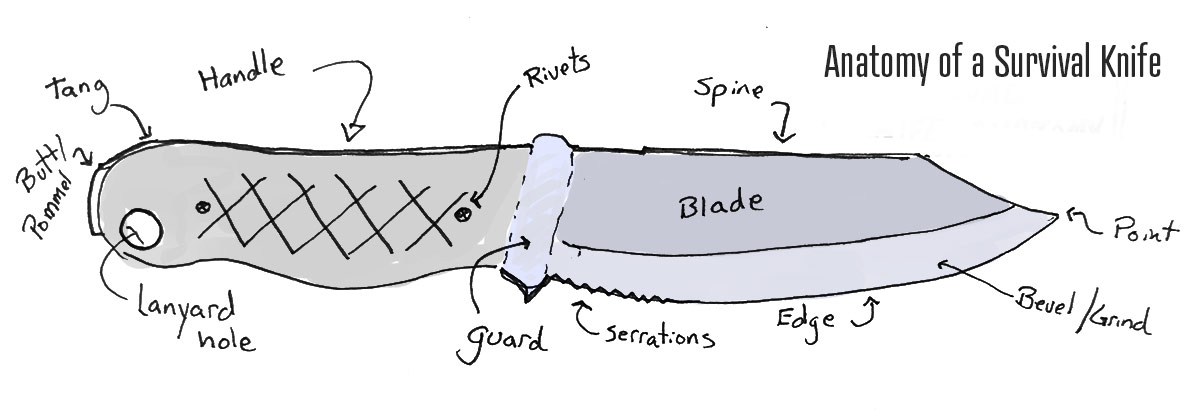

Knife Anatomy

Let’s talk about the basic knife anatomy of what people might refer to as a bushcraft knife or survival knife. Just know there is a lot of variation in these knives too, but in the video I chose the Garberg from Morakniv. This terminology is going to let us talk about the knife properly.

First you have the blade. That’s what cuts. It can be made of lots of types of metal. We’ll get to that in a second.

Most of the time, one side is the cutting edge. The other is the spine.

This is the point.

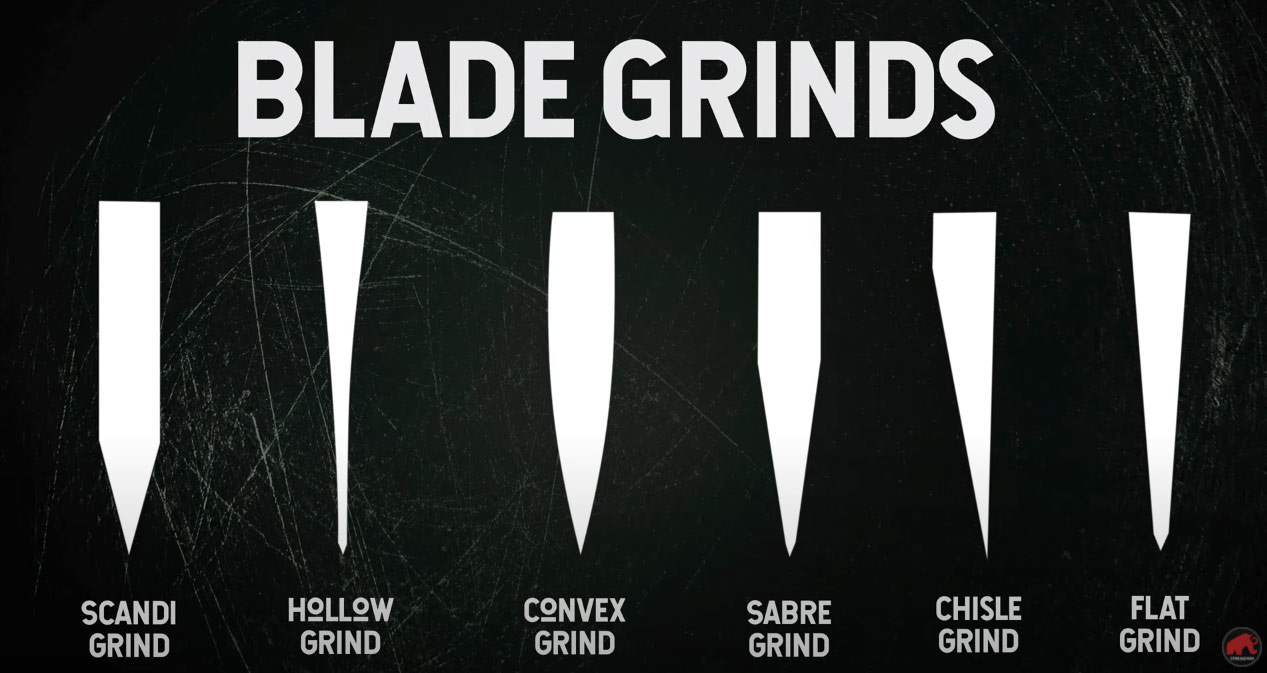

The bevel refers to how the metal is ground to give the cutting edge. More on that in a sec.

Sometimes you have serrations in the knife, which are handy if, say, you’re cutting rope or need to saw through things a bit.

The tang – refers to how far the metal goes into the handle. In this case, it goes all the way through, and is called full tang.

The butt or pommel is at the end, which you can use to point things or say, break glass.

Tang

I want to start with this, because it will help me talk about knife construction. This is a full tang knife the handle just covers the metal. Goes all the way through. It makes it really strong for applications like this – batooning wood. Most of the time that won’t matter, but you wouldn’t want to hammer a ton with a partial tang knife

Metals

How to start. You can make a blade out of almost anything from simple rocks…

… to steel.

Very basically though, steel is technically an alloy of iron. That means it’s this element with other things added for strength. That usually means a bit of carbon – maybe 1-2%. If it’s stainless steel, you get an addition of up to 11% chromium.

Then you have stainless steel. That means it doesn’t rust. So if you’re fishing, or in a kayak you might bring any of these with you. You won’t have to care for them as much.

These blades that are known as carbon steel (even though they both have some carbon in them), will take more care. The benefit is that they’re often stronger, they can be sharpened in the field much easier. They are generally also your sharpest blades. The downside is that it also looses an edge a tad quicker. So you have to maintain them a bit more.

You can also choose laminated steels, like this the core of the blade is made of high carbon steel surrounded by a softer alloyed steel layer. The result is a knife blade with superior toughness and cutting edge retention. Thereby it reaches maximum sharpness and long life.

One last common one is Damascus steel. It’s made from folding up different metals before making the blade. More than anything it’s beautiful.

The EDGE

To get an edge you need to grind the metal down from a flat piece of metal.

Here is the overview of metal grinds. The mora knife I used in the video has a scandi grind. I also showed one of my hollow grinds. I find the scandi is easy to sharpen, so it’s my favorite.

Firestarting

Now sometimes you’ll notice that some knives say they’re good for fire starting. Other say you can’t use a fire starter. That comes down to two things. The main thing is the grind and polishing the spine.

Now I should note why I’m using these mora knives. It’s mostly because I go to Sweden a lot, and Jonas and I competed in the Vasa, which ends in the town of Mora. If you want more information, go check out the rest of our youtube series on bushcraft basics!