Fire can be great for the forest, probably in more ways than you realize. In fact, if you thought fire was bad for the forest then you don’t know the whole truth.

It’s true. Most people view fire as a bad thing for our forests; the media often makes it sound as if a fire in a forest was the worst thing that could ever happen. That’s not always the case, though. Fire can be a good thing. In fact, without fire, we’d lose a lot of plants and animals that are adapted to fire. To help explain this, we went to the United States Forest Service (USFS) Research Group in Athens, Georgia, and made this short video about why fire is actually really good for most forests.

Here are the major take-home messages from the video:

We burn a lot in the South.

In the southeastern US, there are about eight million acres of prescribed burns every year. Compare that to the West which has between 8 and 10 million acres of forests burnt every year. The reasons for the burns are complex, but part of it is to keep our forests healthy and to limit the fuel on the ground.

No fire means more fuel.

Without fire, you leave more fuel on the ground, potentially leading to large, devastating fires. The West is still paying for a century of fire suppression.

Fire helps wildlife.

Some of the species that are helped by fire are quail, turkeys, deer, pygmy rattlesnakes, bob-whites, and the famous red-cockaded woodpeckers, among others.

Fire changes species dynamics in the forest.

There are many species that can tolerate fire. Others depend on fire to complete their life cycle. Pine trees, like the long-leaf pine, are one species that only do well with fire. In fact, just about every stage of their life is adapted to survive a fire. Hardwoods don’t do as well when a fire comes through. That means that forests that have regular burns will start to select for a certain forest type. Traditional forests in the South burnt regularly so if we want traditional forests, they need to be burned.

The South needs fire.

Without fire, we lose our traditional southern pine savannas. The South once used to be covered in these large pine forests—forests with little to no mid-story. It was a grass savanna with big pine trunks sticking out of them. Fire would crawl through these grasses, burning them every one to five years on average. This kept the hardwoods at bay and made for a completely unique ecosystem.

Fire Science and Scientists

Fire scientists come from diverse backgrounds. You can be an ecologist, a biologist, a physicist, or a meteorologist. Scientists that study fire help make informed management decisions. Firefighters on the ground have learned how to make fires and let them spread across the landscape; the scientists are there to help us understand why the burns are important.

Here are a handful of scientists that we talked to in order to make this film. We interviewed each one, so be sure to click on their profiles to learn more about them.

Scott Goodrick, Meteorologist

It might not seem obvious why having a meteorology degree would help in fire science. However, in today’s crowed and urban world, we have to keep the harmful effects of smoke far away from urban centers. To make sure that happens, it’s important to control the smoke from prescribed burns so that it heads up and instantly starts mixing with the atmosphere. That’s where Scott’s research comes in. I got to find out some of the more interesting ways that fire affects people. Read Scott’s interview.

Louise Loudermilk, Fire Scientist/Ecologist

Part of being an ecologist is studying how the natural world works. Louise makes models that try to predict what’s happening in the ecosystem. In particular, she uses models to try to understand fire. How does fire effect the next diversity in an ecosystem? Read Louise’s interview.

Dexter Strother, PhD Candidate and Fire Scientist

Dexter is one of the most enthusiastic and quick-witted fire scientists we ran into at the Athens lab. He is a PhD candidate (meaning he is doing his research to get his doctorate degree) at Georgia Tech. Other than working with the USFS to understand fire and help with burns, he studies black carbon. Don’t really know what that is? Check out his profile for more. Read Dexter’s interview.

Joe O’Brien, Fire Ecologist

Joe is a hardcore plant ecologist. He first studied ecology in the rainforests of Costa Rica. Now, instead of studying the wet tropical rainforests, he studies fire. Fire, he has found, is one of the key ingredients in maintaining the high diversity in traditional southern pine savannas. Read Joe’s interview.

Ben Hornsby, Fire Research Specialist

Ben spends a lot of his time driving around the forests and working with the fire managers. He serves as a go-between for the other researchers and the fire managers. Read Ben’s interview.

More Fire Science via Twitter

- Cathelijne Stoof @dr_firelady

- Cameron Balog @FireManagement

- Southeast Rx Fire @SE_RxFire

Recommended Books about Fire Ecology

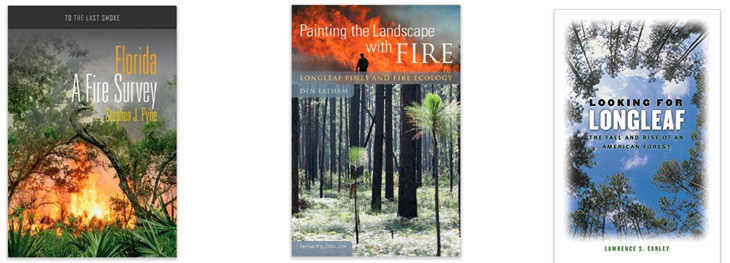

To research this video and the topic of fire, we read three books. I highly recommend all three. They all complement each other and talk about slightly different aspects of fire in southern forests.

- Florida: A Fire Survey

- Painting the Landscape with Fire: Longleaf Pines and Fire Ecology

- Looking for Longleaf: The Fall and Rise of an American Forest

A Quick Fire Overview

Here is a quick overview of the lessons learned: 8 Things to Know About Fire. I made this in case educators want to show a different version of the video in class.

Want to study fire?

We need more great fire scientists in the world. If you’re interested in becoming a fire scientist, make sure to read each of the bios above. We made a special effort to ask each person what advice they have for those wanting to study fire. Also, because the USFS spends over half its budget every year on fire science, one of the best places to start looking for work is through the USFS in your area. Here is a great link to information on jobs from them.