If you were a shark, what would you be.

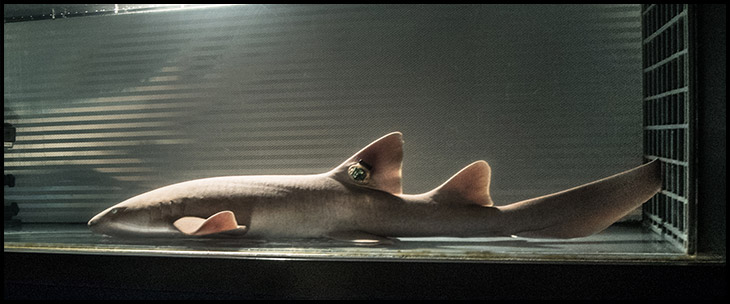

If I was a shark I think that I would enjoy being a nurse shark, because, let’s be honest, I love taking naps, and nurse sharks seem to have developed a pretty successful lifestyle centered around that tenet , which is a pretty cool adaptation in its own right.

Could you summarize what you do for research?

I’ve spent the past few years working at Mote Marine Laboratory with Dr. Nick Whitney using data-logging tags to study the physiology and behavior of a variety of sharks. I recently moved to Australia to start my PhD and am doing similar work here, using accelerometers to study how temperature affects the behavior, movements, and activity patterns of juvenile sawfish and bull sharks. In particular I am looking at how changes in temperature resulting from climate change might impact these populations in the future.

What does a typical field day look like?

Generally my field days fall into two categories: catching and tagging sharks, and getting the shark tags back. We usually use gill nets to capture small sharks and sawfish, and longlines, drumlines, or rod and reel to capture bigger sharks. Once we catch the sharks, we measure them, attach the data-logging tags, blood sample them or take any other samples we need, and then release them again. Most of the tags that I have used are data-logging tags, which means that they record data to memory and need to be physically recovered in order for us to look at the data. For smaller sharks that stay in one area, we can track and recapture them to get the tags back, but it is almost impossible to recapture large sharks that can travel long distances quickly. So, when we are tagging larger sharks, we build these tags into float packages with radio tags in them that will pop-off the sharks a few days after release, at which point I go back out on the water and listen for the floating tags with an antenna, track them down, and retrieve them.

What inspired you to start doing this?

I grew up in Seattle near the ocean and have been interested in marine biology since I was a kid, when one of my favorite things to do was to go searching through rocky tidepools for cool invertebrates. I had a neighbor who worked for NOAA, and when I was in middle school she started taking me out with her on trawl surveys in the Puget Sound, where we caught all sorts of different kinds of fish, and I got to help sort through the catch and do fish dissections. I absolutely loved it, and have pursued my interest in marine research ever since, eventually leading me to sharks.

Why do you think it’s important?

Because they are top predators, sharks hold a very important position in their ecosystems, balancing the entire food web below them. I think that it is important to study sharks, and especially how they are impacted by human-driven activities including fishing and climate change, in order to figure out how to best work with and protect these animals so that they can continue to help maintain healthy oceans for all of us.

What is the hardest thing about doing this?

I think that the hardest thing about doing research is working through the hundred small challenges and steps between collecting your data in the field and translating that through statistics into an understandable story.

What is the most rewarding thing about it?

The thing that I find most rewarding about my research is figuring out new and creative ways to use or acquire data. Knowing that the data I get back will also help to better understand and protect a pretty cool animal isn’t bad either!

What if others want to help in shark conservation – how can they help?

I think that the best way to help in shark conservation is to be well informed about what is going on in your oceans, and to help spread knowledge about shark conservation and ocean conservation in general. There are a lot of little everyday things that people can do to help maintain healthy oceans, from making sure you throw away your trash at the beach to quickly releasing sharks caught for recreation, or using hooks or fishing methods that are friendlier to ocean critters, but not everybody recognizes these. Being well informed and helping to spread knowledge within your community and beyond is a huge step in the right direction.

Finally, do you have any advice for a young student wanting to study something like this? What would you tell them?

My best advice is to be persistent! Shark research is a pretty competitive field and it can be hard to get your foot in the door and find a internship or job, but if you are passionate about what you are doing, stick with it, and work hard, there are lots of good opportunities out there.