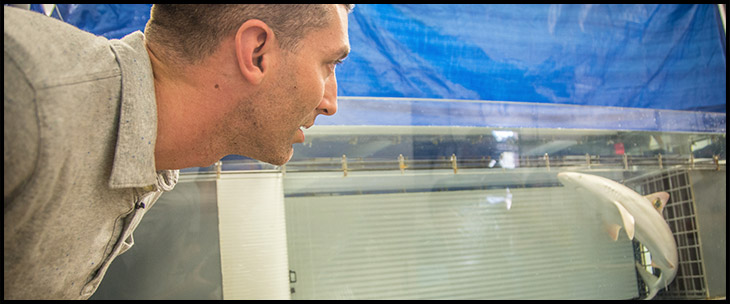

Nick runs a lab at Mote Marine laboratory in Sarasota, FL. He studies shark behavior and physiology using, among other things, accelerometers. It’s really neat research that I’ve had the pleasure of documenting several times. I met Nick in Hawaii as a grad student there and I’ve been following his work ever since. He’s also one of the funniest researchers I know. If you don’t know Nick already, check out this short video and read the answers we asked him here.

If you were a shark, what would you be?

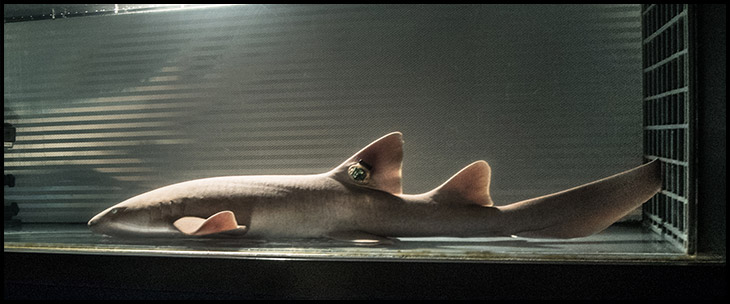

I would be a nurse shark because I love coral reefs and warm water. I am also slow, but prosperous, and I have many offspring.

Could you summarize what you do for research?

Most of my work involves trying to figure out what wild animals do when we can’t observe them directly. To do this, we use a number of tools to “spy” on the animals. Most of these tools come in the form of tags that we attach to the animals. Our most commonly used tag right now is the acceleration data logger, a device that uses the same technology found in Fitbits, smartphones, and video game controllers to monitor every movement that an animal makes for days – or sometimes weeks – at a time. They record about 100 acceleration data points every second, and also record fine-scale depth and temperature. This is all far too much data to be transmitted to us so the data are stored to memory and the tag itself has to be physically recovered to get the data. This is a big challenge but, amazingly, it usually works! See our videos with Untamed Science for more details on this process.

What does a typical field day look like?

Some days in the field involve going out with commercial longline fishermen and measuring, blood-sampling, and tagging dozens of sharks in a day. Other times we go out with recreational fishermen and may only catch one or two sharks in a day, although we still have a lot of fun. Tag recovery days involve long hours of riding in a fast boat all over the ocean, finding and recovering tags that have popped off of sharks at pre-set times. My favorite field days are in tropical places like the Florida Keys when we use kayaks for transport and get in the water to observe sharks directly. Those days make me feel like I’ve chosen the right career!

What inspired you to start doing this?

I was fascinated with (and terrified of!) sharks from a young age as a kid growing up far from the ocean in southern, central Michigan. As an undergrad at Albion College (Michigan) I had the opportunity to work with Dr. Jeff Carrier, one of the truly great mentors in the field of shark research. Jeff’s guidance and encouragement was the main factor that put me on my career path. He also put me in the field in the Florida Keys with live sharks and a guy named Wes Pratt, all of which were fascinating creatures that I had never been exposed to before. After that I was convinced that being a shark scientist was the only thing I ever wanted to do.

Why do you think it’s important?

Sharks are important because they appear to play a disproportionately large role in maintaining stability in many marine ecosystems. They’re also important because they’re cool, and I don’t say that lightly. It can be very difficult to convince people in Michigan or Ohio or Nebraska that healthy oceans are vitally important for all of us, including them. We may never be able to get them interested in diatoms or sponges, but if we can use sharks and other (wait for it…) “charismatic megafauna” to get their attention and raise their awareness of marine conservation issues, that may be even more important than the specific research questions we’re addressing.

What is the hardest thing about doing this?

The hardest part about this work is getting funding, and finding the time to address all of the interesting questions that need to be addressed. The fieldwork and desk work also have their own unique challenges. Analyzing data and writing proposals and papers requires long hours of deep focus that can be hard to come by when you have a lot of other responsibilities. The fieldwork is a constant battle to coordinate schedules and find the right windows of good weather to complete the work. I’m also prone to seasickness, which is one of the worst feelings in the world, but having a large, thrashing shark in front of you is a great distraction from it.

What is the most rewarding thing about it?

The most rewarding thing to me is when we’re able to use our tags to discover things that we had no idea were going on and never could’ve figured out in any other way. Sturgeon will lie on the bottom upside down for an hour when they’re stressed out. Great hammerheads spend long periods swimming in a sideways orientation. Nurse sharks swim up and down in the water column like a marlin when they’re traveling. These are all things that I didn’t even believe were real the first time I saw them in our data (and in some cases I accused the tag manufacturers of sending us faulty equipment!). But they are real, and fascinating, and these “WOW” moments are definitely the most rewarding part of the job.

What if others want to help in shark conservation – how can they help?

I love the answers about this from the other scientists profiled on this site. Learn about the real issues facing sharks and our oceans, not just the bumper sticker issues thrown out in the last 30 seconds of the Shark Week show. Follow shark scientists on twitter. The ones listed on this website are a great start, but I would also add several others, particularly @whysharksmatter and @SharkAdvocates, who is on the front lines of the most pressing issues to protect sharks around the world.

Finally, do you have any advice for a young student wanting to study something like this? What would you tell them?

First I would tell them don’t do it. It doesn’t pay well compared to a lot of other careers, it requires a lot of schooling, and it’s a very competitive field. If you are at all interested in a career in business or something that makes money, you should do it, because we need strong ocean advocates in other walks of life far more than we need more marine biologists! But if you are certain that a career in marine science is the only thing for you, then I would say that persistence is the most important quality. Find people that are doing great work in the field and try to work with them – for free if necessary – so you can learn the ropes and build your resume. Science and math skills are important but writing and communication skills are more important. Do great work and don’t worry about whether you get recognition for it or not, you will in the long run. And when someone helps you along the way, be grateful and SAY THANK YOU! You will be shocked at how many people fail to do this.

Videos With Nick Whitney

We’re making a series of videos about Nick’s Shark Research. Here are a couple more good ones to watch.