White-nosed Syndrome in Bats

While most people are sleeping, large numbers of bats are busy feeding on insects in North America. Unfortunately, some of these populations of bats are facing large die-offs due to the spread of a disease known as white-nose syndrome.

The Disease

White-nose syndrome (WNS) was first observed in New York in 2006 and has killed over 5.7 million bats in North America in the last 10 years. It has spread quickly and is confirmed in 29 states and 5 Canadian provinces. It’s believed WNS was accidentally introduced to the US from Europe by humans.

It is named white-nose syndrome because the fungus that causes it (Pseudogymnoascus destructans) often appears in white patches on the noses and wings of infected bats. WNS causes infected bats to be active when they would normally be hibernating, resulting in a loss of their winter fat reserves. Without these fat reserves, the bats are unable to survive the winter. Bats dead from the disease have been found in large numbers in caves. Often less than 10% of the bats in an infected cave survive.

How It Spreads

The spores from the fungus are easily spread by animals and humans. If a bat travels from an infected cave to a new cave, it is likely bringing spores with it. Researchers and explorers who enter an infected cave have to take great care in cleaning all of their clothing and equipment to prevent spreading the fungus themselves.

Species Affected

Seven bat species have been diagnosed with WNS:

- Little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus)

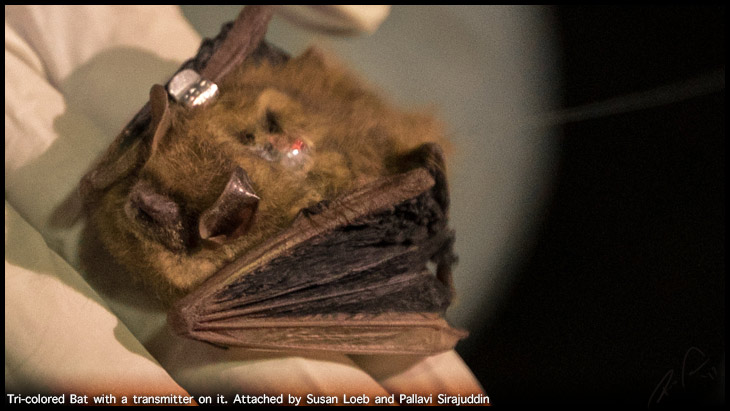

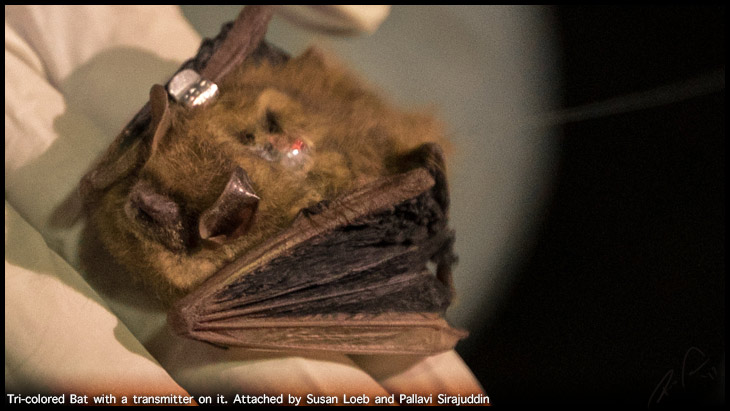

- Tri-colored bat (Perimyotis subflavus)

- Northern long-eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis)

- Big brown bat (Eptesicuc fuscus)

- Gray bat (Myotis grisescens)

- Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis)

- Eastern small-footed bat (Myotis leibii)

The little brown bat was once the most common bat in the northeastern US, but very few now remain in that region due to WNS. Two other species, gray bats and Indiana bats, are endangered also, putting their populations at a high risk of extinction.

Resistant Species

Five North American species have been found with the fungus on them that causes WNS but show no symptoms of the disease. It’s possible that these species are resistant to the disease. They include:

- Eastern red bat (Lasiurus borealis)

- Sountheastern bat (Myotis austroriparius)

- Silver-haired bat (Lasionycteris noctivagans)

- Rafinesque’s big-eared bat (Corynorhinus rafinesquii)

- Virginia big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii virginianus)

Bats in Europe, where the fungus is believed to have been present for a long time, are apparently immune to the disease.

Research Controversy

There is some disagreement in the research community about the best way to continue monitoring the bats threatened by WNS. Some researchers continue to study bats during their winter hibernation in order to test the bats for the presence of the fungus and observe and symptoms of the disease. Every time a bat is disturbed during hibernation, it burns off some of its winter fat stores, putting it at greater risk of not having enough fat to survive the winter.

Many researchers agree that the focus should shift to studying populations that have survived WNS. These survivors may have something in common with the immune European populations.

The Future

Protecting the survivors of WNS and minimizing disturbances to these populations during winter is the best option we have to help these bats survive and hopefully return the affected species to pre-WNS numbers.

Resources on the Web

Related Topics

While most people are sleeping, large numbers of bats are busy feeding on insects in North America. Unfortunately, some of these populations of bats are facing large die-offs due to the spread of a disease known as white-nose syndrome.

The Disease

White-nose syndrome (WNS) was first observed in New York in 2006 and has killed over 5.7 million bats in North America in the last 10 years. It has spread quickly and is confirmed in 29 states and 5 Canadian provinces. It’s believed WNS was accidentally introduced to the US from Europe by humans.

It is named white-nose syndrome because the fungus that causes it (Pseudogymnoascus destructans) often appears in white patches on the noses and wings of infected bats. WNS causes infected bats to be active when they would normally be hibernating, resulting in a loss of their winter fat reserves. Without these fat reserves, the bats are unable to survive the winter. Bats dead from the disease have been found in large numbers in caves. Often less than 10% of the bats in an infected cave survive.

How It Spreads

The spores from the fungus are easily spread by animals and humans. If a bat travels from an infected cave to a new cave, it is likely bringing spores with it. Researchers and explorers who enter an infected cave have to take great care in cleaning all of their clothing and equipment to prevent spreading the fungus themselves.

Species Affected

Seven bat species have been diagnosed with WNS:

- Little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus)

- Tri-colored bat (Perimyotis subflavus)

- Northern long-eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis)

- Big brown bat (Eptesicuc fuscus)

- Gray bat (Myotis grisescens)

- Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis)

- Eastern small-footed bat (Myotis leibii)

The little brown bat was once the most common bat in the northeastern US, but very few now remain in that region due to WNS. Two other species, gray bats and Indiana bats, are endangered also, putting their populations at a high risk of extinction.

Resistant Species

Five North American species have been found with the fungus on them that causes WNS but show no symptoms of the disease. It’s possible that these species are resistant to the disease. They include:

- Eastern red bat (Lasiurus borealis)

- Sountheastern bat (Myotis austroriparius)

- Silver-haired bat (Lasionycteris noctivagans)

- Rafinesque’s big-eared bat (Corynorhinus rafinesquii)

- Virginia big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii virginianus)

Bats in Europe, where the fungus is believed to have been present for a long time, are apparently immune to the disease.

Research Controversy

There is some disagreement in the research community about the best way to continue monitoring the bats threatened by WNS. Some researchers continue to study bats during their winter hibernation in order to test the bats for the presence of the fungus and observe and symptoms of the disease. Every time a bat is disturbed during hibernation, it burns off some of its winter fat stores, putting it at greater risk of not having enough fat to survive the winter.

Many researchers agree that the focus should shift to studying populations that have survived WNS. These survivors may have something in common with the immune European populations.

The Future

Protecting the survivors of WNS and minimizing disturbances to these populations during winter is the best option we have to help these bats survive and hopefully return the affected species to pre-WNS numbers.