Salmon Shark

Lamna ditropis

You might think you wouldn’t stand a chance of seeing any big sharks if you’re far north in the Pacific. After all, big sharks live in warmer waters around places like Hawaii, Australia, and California, right?

Wrong. In fact, the north Pacific is home to plenty of large sharks. One of the most common is the salmon shark (Lamna ditropis) named after its favorite prey—you guessed it—salmon.

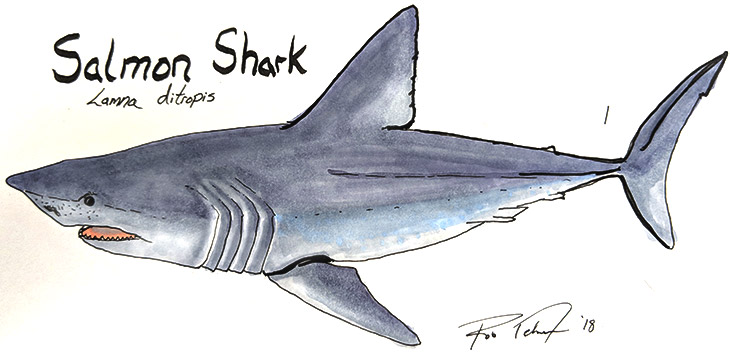

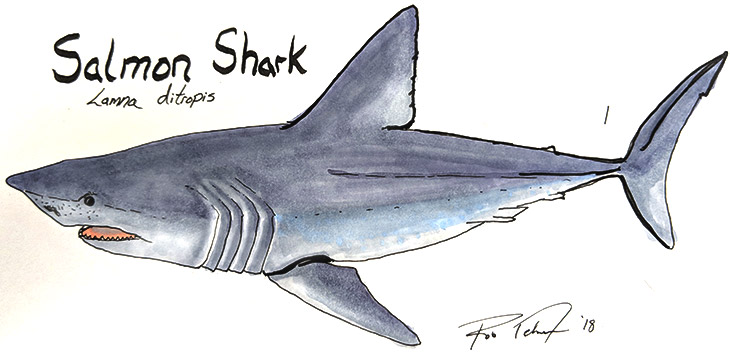

What do salmon sharks look like?

The salmon shark is the doppelganger of the porbeagle shark (Lamna nasus). They look almost identical, growing up to 12 feet long with a dark grayish back and a lighter underbelly. While the porbeagle hangs out in the north Atlantic, the salmon shark prefers the cool waters of the north Pacific.

It’s likely that these shark species evolved from the same ancestor. Whereas one population ended up on one side of the Americas, another population ended up on the other side. Since they are unlikely to swim through warm waters to reach the other side of the continents and intermix, they have stayed separate and diverged into two distinct (but very similar) species.

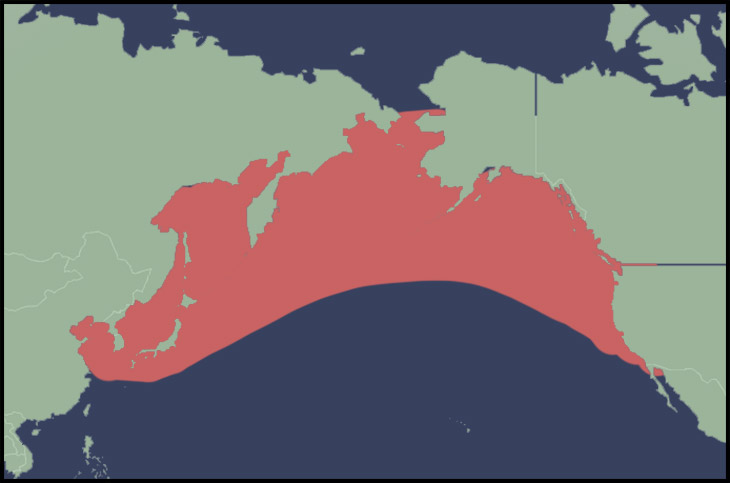

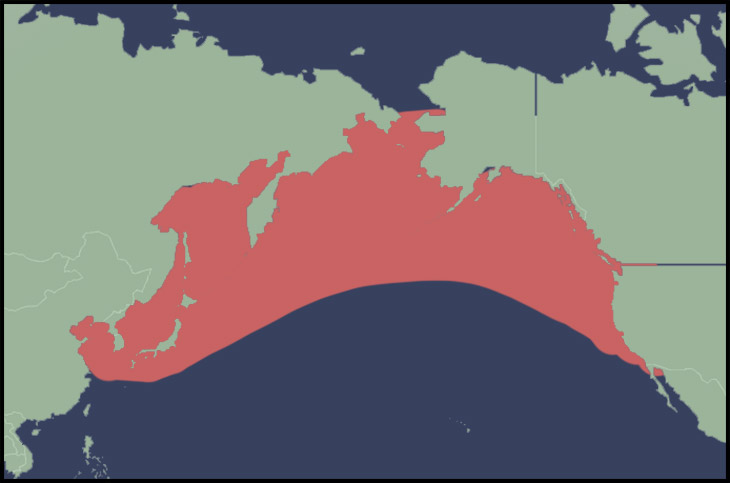

Where do salmon sharks live?

You can come across salmon sharks almost anywhere in the north Pacific, whether you’re close to shore or out in the open ocean.

Salmon sharks show an interesting pattern in sexual segregation (i.e., males and females form separate groups). The further north you go, the more the two sexes stay away from each other. Females hang out more in the northeastern Pacific, while males swim around in the northwestern Pacific.

How do salmon sharks reproduce?

When it comes to reproduction, salmon sharks have a similar gestation period to humans: nine months. Breeding takes place around August and September, so pups are born in spring and early summer. A female salmon shark can breed about every two years.

That’s where the similarities end though. Salmon sharks reproduce via aplacental viviparity. After breeding, a female will carry a bunch of fertilized eggs in her uterus. After hatching in utero, the biggest pups will actually eat their fellow siblings until just two to five pups remain. (It gives a whole new meaning to sibling rivalry!) Surviving pups are born fully-formed and ready to live on their own.

What do salmon sharks eat?

Salmon sharks do indeed eat a lot of salmon. According to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, in 1998 salmon sharks were responsible for eating up to a full quarter of the annual run of salmon in Prince William Sound!

When they’re not chowing down on salmon, however, they’re like most sharks and will eat basically anything that can fit into their mouth. There are no official recorded attacks on humans by salmon sharks, but theoretically it is possible because they are so large. But don’t let that scare you—check out the video of people swimming with salmon sharks below:

Salmon Sharks: Masters of Countercurrent Heat Exchange

Sharks are generally considered ectothermic, meaning that they are cold-blooded and take on the same temperature as the surrounding environment. That poses a problem for salmon sharks that swim around in the super-chilly water at the high latitudes they prefer. So, they’ve come up with a solution: they’re partially endothermic, a trait that allows them to heat up their body to a certain degree!

The way salmon sharks do this is with countercurrent heat exchangers. (It sounds more like a high-tech racing car feature than shark trait.) This feature manages the animal’s body heat using blood vessels laid out in a specific pattern.

Blood coming from the shark’s exterior vessels is very cold, since it’s been right next to the chilly water. Blood coming from the shark’s inner body is usually a bit warmer, since it has been warmed by the muscles. In salmon sharks, the cold blood vessels coming from the exterior are laid out next to the warm blood vessels coming from the muscles. This heats up the incoming blood. (Kind of how department stores manage in the winter: you walk through the doors and receive a blast of hot air to warm you–and the air coming in with you–fast.)

This special trick is what gives salmon sharks (and their porbeagle doppelgangers) an edge over their prey. Warm muscles (up to 20ºF warmer than the surrounding water) allow them to swim just a bit faster than the icy salmon, so they’re able to chomp them up like a ruthless, finned Pac-Man.

How are salmon shark populations doing?

The status of salmon sharks is one of the happier conservation stories in the shark world. They’re not widely sought after by commercial or sport fishermen, except for a very small sport fishery in Alaska. They are caught as bycatch by commercial fisheries, but studies have shown that their populations are stable, so fishing doesn’t seem to be especially detrimental.

Even though the news is good now, these amazing sharks will always require monitoring. They are slow-growing and give birth to just a few pups at a time, so it would be easy for salmon sharks to become vulnerable in the future if their populations did decline. But for now, we can rest easy that these cool creatures are doing just fine.

Related Topics

You might think you wouldn’t stand a chance of seeing any big sharks if you’re far north in the Pacific. After all, big sharks live in warmer waters around places like Hawaii, Australia, and California, right?

Wrong. In fact, the north Pacific is home to plenty of large sharks. One of the most common is the salmon shark (Lamna ditropis) named after its favorite prey—you guessed it—salmon.

What do salmon sharks look like?

The salmon shark is the doppelganger of the porbeagle shark (Lamna nasus). They look almost identical, growing up to 12 feet long with a dark grayish back and a lighter underbelly. While the porbeagle hangs out in the north Atlantic, the salmon shark prefers the cool waters of the north Pacific.

It’s likely that these shark species evolved from the same ancestor. Whereas one population ended up on one side of the Americas, another population ended up on the other side. Since they are unlikely to swim through warm waters to reach the other side of the continents and intermix, they have stayed separate and diverged into two distinct (but very similar) species.

Where do salmon sharks live?

You can come across salmon sharks almost anywhere in the north Pacific, whether you’re close to shore or out in the open ocean.

Salmon sharks show an interesting pattern in sexual segregation (i.e., males and females form separate groups). The further north you go, the more the two sexes stay away from each other. Females hang out more in the northeastern Pacific, while males swim around in the northwestern Pacific.

How do salmon sharks reproduce?

When it comes to reproduction, salmon sharks have a similar gestation period to humans: nine months. Breeding takes place around August and September, so pups are born in spring and early summer. A female salmon shark can breed about every two years.

That’s where the similarities end though. Salmon sharks reproduce via aplacental viviparity. After breeding, a female will carry a bunch of fertilized eggs in her uterus. After hatching in utero, the biggest pups will actually eat their fellow siblings until just two to five pups remain. (It gives a whole new meaning to sibling rivalry!) Surviving pups are born fully-formed and ready to live on their own.

What do salmon sharks eat?

Salmon sharks do indeed eat a lot of salmon. According to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, in 1998 salmon sharks were responsible for eating up to a full quarter of the annual run of salmon in Prince William Sound!

When they’re not chowing down on salmon, however, they’re like most sharks and will eat basically anything that can fit into their mouth. There are no official recorded attacks on humans by salmon sharks, but theoretically it is possible because they are so large. But don’t let that scare you—check out the video of people swimming with salmon sharks below:

Salmon Sharks: Masters of Countercurrent Heat Exchange

Sharks are generally considered ectothermic, meaning that they are cold-blooded and take on the same temperature as the surrounding environment. That poses a problem for salmon sharks that swim around in the super-chilly water at the high latitudes they prefer. So, they’ve come up with a solution: they’re partially endothermic, a trait that allows them to heat up their body to a certain degree!

The way salmon sharks do this is with countercurrent heat exchangers. (It sounds more like a high-tech racing car feature than shark trait.) This feature manages the animal’s body heat using blood vessels laid out in a specific pattern.

Blood coming from the shark’s exterior vessels is very cold, since it’s been right next to the chilly water. Blood coming from the shark’s inner body is usually a bit warmer, since it has been warmed by the muscles. In salmon sharks, the cold blood vessels coming from the exterior are laid out next to the warm blood vessels coming from the muscles. This heats up the incoming blood. (Kind of how department stores manage in the winter: you walk through the doors and receive a blast of hot air to warm you–and the air coming in with you–fast.)

This special trick is what gives salmon sharks (and their porbeagle doppelgangers) an edge over their prey. Warm muscles (up to 20ºF warmer than the surrounding water) allow them to swim just a bit faster than the icy salmon, so they’re able to chomp them up like a ruthless, finned Pac-Man.

How are salmon shark populations doing?

The status of salmon sharks is one of the happier conservation stories in the shark world. They’re not widely sought after by commercial or sport fishermen, except for a very small sport fishery in Alaska. They are caught as bycatch by commercial fisheries, but studies have shown that their populations are stable, so fishing doesn’t seem to be especially detrimental.

Even though the news is good now, these amazing sharks will always require monitoring. They are slow-growing and give birth to just a few pups at a time, so it would be easy for salmon sharks to become vulnerable in the future if their populations did decline. But for now, we can rest easy that these cool creatures are doing just fine.