American Black Bear

Ursus americanus

In North America, the black bear (Ursus americanus) is the most common species of bear. It is native to the continent and ranges from northern Alaska to Mexico. In fact the black bear is found in 41 of the 50 states in the U.S.A. While the brown bear is Eurasian in origin, the black bear is currently thought to have evolved in North America about two million years ago. Here is quick video clip talking about black bear hibernation. In fact, we helped with a small study with the Michigan DNR.

Life History Characteristics

Black bears are usually solitary animals whose lifestyles are dictated by their biological need to consume large quantities of food. Bears only tolerate the presence of other bears during the breeding season, when a female is with her cubs, or when bears congregate in areas with concentrated food sources such as garbage dumps and salmon streams. Adult male bears are not part of the family unit.

Reproduction

Bears reproduce at a very low rate compared to other North American land mammals. Female black bears usually become sexually mature between the ages of two and seven years. The age of first reproduction varies geographically, depending on the availability of food and the size and condition of the bears. Males (called boars) and females (called sows) may mate with more than one partner. The mating period usually occurs in June or July and lasts from two to five days. During this time, males roam extensively in search of receptive females. Implantation of the fertilized eggs in the uterine wall does not occur until the female is ready to enter the den, usually in October (in northern regions) or November (in central regions). This phenomenon is called delayed implantation. If a female does not gain enough weight before hibernation, her body may reabsorb the eggs.

Birth and Growth of Cubs

Cubs are born in the den during January or February and emerge from the den in April. Litter size can range from one to five cubs, with two-cub litters the most common. Older or heavier black bears often produce more offspring. Newborn cubs weigh seven to 11 ounces (200 to 300 grams). By six weeks of age, cubs weigh about four to seven pounds (two to three kg). Newborn cubs are altricial (helpless at birth). Their eyes are closed, and they are covered with fine, down-like fur. Because bears are mammals, the first meal they receive in life is rich milk from their mothers. Bear cubs grow rapidly because bear milk has a very high fat and protein content. Cubs nurse while they are in the den and may continue nursing through the summer.

Cubs remain with their mothers for about a year and a half. During this time, they learn fundamental skills from their mothers. These early learning experiences shape a cub’s future behavior. Throughout life, bears also learn by trial and error and by observing other bears. Eighteen months after the cubs are born, the family unit breaks up. Cubs, now called yearlings, begin searching for their own home ranges. Female yearlings usually remain within or near their mothers’ home range, but male yearlings must find territories to claim as their own. Dispersal is a difficult and dangerous time. Although black bears have few natural predators, adult male bears will kill and eat yearlings. Since dominant males occupy the best habitats, younger male bears are often pushed into marginal habitats. Frequently, marginal habitats are close to rural homes, towns, or cities. As a result, young male bears have a higher risk of mortality from vehicle collisions, hunting, and negative encounters with humans.

Mortality

Diseases rarely impact black bears. However, dental cavities are common due to their sugar-rich diet. Young or smaller bears are occasionally preyed upon by brown (grizzly) bears, wolves, bobcats, and other black bears. Once bears reach maturity at four to eight years of age, hunting, trapping, poaching, and vehicle collisions are the main causes of death. Vehicle mortality may be higher than reported because bears can sustain mortal injuries and continue to travel considerable distances from roadways. Male bears suffer higher vehicle mortality than females because of their larger home ranges, in combination with their habit of crossing and following roadways. In remote wild areas, black bears can live up to 30 years.

Behavior

Black bears are highly curious, very intelligent, mobile, and adaptable animals. They quickly learn by trial and error, adapting to new stimuli and circumstances. For example, one study indicated that bears near urban/wild land edges were active fewer hours each day, entered their dens later, remained in them for fewer days, and shifted their activities to nocturnal periods. Curious black bears will explore and learn about novel objects in their environment by manipulating them with their forepaws and by chewing. Bears can also learn from other bears; bear cubs learn many behaviors by watching their mother.

Like most animals, black bears exhibit certain behaviors that can sometimes forecast their mood or intentions. A black bear standing on its hind legs is often curious, and is trying to see or hear better. A nervous black bear may salivate excessively. A frightened black bear may run off or act defensively, giving visual and vocal cues such as swatting the ground with its paw or blowing explosively through its nostrils.

Other defensive displays by a bear may include huffing, moaning, jaw popping, or lowering its head with its ears drawn back while facing the danger. Black bears’ metabolic need to eat a year’s worth of food in seven to nine months significantly affects their behavior. Hungry black bears may roam farther than usual in search of food, sometimes beyond the normal range of the species.

Black Bear Populations

In many areas of the county, black bear populations have recovered from historic lows. Beginning in the late 1980s through the start of the 21st century, black bear numbers increased at a rate of two percent a year continent wide. Changes benefiting black bears during this time included reforestation of the landscape, black bear reintroduction programs, and regulations on hunting black bears.

Though black bears have not reclaimed all of their original range across America, they have rebounded to populations of an estimated 800,000 bears in 37 states and all Canadian Provinces. At the same time, human populations have expanded, numerically and geographically. In some areas, these two expanding populations are intersecting. In overlapping habitats, humans can often coexist with black bears. The challenge is to find a balance between the number of black bears a habitat can support, called the biological carrying capacity, and the number of bears the human community will accept, called the cultural carrying capacity.

Coexisting with Black Bears

A key factor in predicting a person’s attitudes towards black bears is his or her perception of how dangerous bears are. Familiarity fosters positive attitudes. In New York State, a 2002 mail survey indicated the majority of residents enjoyed having black bears in the state. Most survey respondents had seen a wild black bear and almost all perceived it as a positive experience. Negative attitudes towards black bears are often related to concerns for personal safety, reactions to bear damage to crops or property, and beliefs centering on real or perceived competition for game and habitat.

If you want to know how to survive a black bear attack at some point, head over to StoneAgeMan.

Human behaviors that can benefit black bear populations include habitat restoration and conservation programs, land use planning to limit habitat fragmentation, research and management programs, and wildlife education programs. Human behaviors that negatively affect black bears include feeding bears, harassing bears, land development in “bear country,” human activities that reduce natural bear food sources, and management strategies that affect other wildlife species that compete for resources (i.e. White-tailed deer).

Subspecies of Black Bear:

There are several different subspecies of black bear including the Cinnamon Bear, Glacier Bear, and Kermode Bear. The following list describes some of the accepted subspecies.

Ursus americanus altifrontalis

This subspecies lives in the Pacific NW from central BC to northern Cal and inland to Northern Idaho.

Ursus americanus amblyceps

Found in CO, NM, AZ, west TX, southeaster Utah and northern Mexico.

Ursus americanus americanus

This subspecies is widespread from eastern MT to the east coast. Its found as far north as Alaska and south to TX.

Ursus americanus californiensis

This California bear is found in the mountains from southern Oregon to southern CA.

Ursus americanus carlottae

The Queen Charlotte Black Bear is found on the Queen Charlotte Islands and the Alaska mainland.

Ursus americanus cinnamomum

The Cinammon Bear is found in ID, western MT, WY, eastern WA, northeastern UT and OR.

Ursus americanus emmonsii

Found in southeastern AK

Ursus americanus eremicus

Lives in northeastern Mexico

Ursus americanus floridanus

In the south this bear ranges from FL, southern Georgia to Alabama.

Ursus americanus hamiltoni

This bear lives on the island of Newfoundland

Ursus americanus kermodei

The Kermode Bear lives on the central coast of British Columbia

Ursus americanus luteolus

Found natively in eastern TX, LA, and southern MS

Ursus americanus machetes

Native to north-central Mexico

Ursus americanus perniger

Native to the Kenai Pennisula, AK

Ursus americanus pugnax

Found on the Alexander Archipelago in AK

Ursus americanus vancouveri

Bear History

Before Columbus

When humans first entered North America some 15,000 years ago, bears inhabited every corner of the continent. The grizzly bear thrived in all western states, ranging as far south as Mexico and as far north as the tip of Alaska. Related to the grizzly bear, but with certain behavioral, morphological, and physiological differences, the smaller black bear roamed North America from the Atlantic to the Pacific and from Mexico to the northern edges of the continent. To Native Americans, the black bear provided a valuable source of thick hides for clothing and shelter, rich meat, and sweet fat. The unique traits of the bear itself provided the essence of their legends. Native Americans pass on these legends through an oral tradition called storytelling. These stories teach the young, pass on a tribe’s rituals and beliefs, safeguard history, and entertain the listeners. Some stories describe how an animal acquired a physical characteristic while others tell about the animal’s relationships with people or other wildlife.

Pioneers Arrive

Early American settlers found black bears in abundance when they arrived, but the bears represented more than a food source to early pioneers. Settlers brought with them European perceptions and behaviors; wilderness was viewed as threatening, as were the wild animals living in it. Bounties placed on predators became common, such as the one-penny bounty for a dead wolf in Massachusetts Bay Colony. To the settlers, bears posed threats to their families, livestock, crops, and future. This attitude surfaced in popular nature books of that time which showed animals such as bears attacking hunters or eagles flying off with children. Settlers did not just kill bears with their guns. Cutting, burning and clearing changed the wooded lands into open farm fields and pastures. As the wave of humans expanded, black bears lost much of their native habitat, restricting their populations to some of the more mountainous, swampy, and rugged regions of North America.

Conservation Awakens

The few black bears that remained in the mid 1800s came under the pressure of unregulated market hunting for their hides, meat, and fat. Due to their low reproductive rate, bears recover more slowly from population losses than other North American mammals. By 1900, black bear numbers dwindled in many areas of the country, nearing the point of extinction. Eventually, America began to realize the importance of wildlife management, including the plight of the black bear. By the mid-1900s, hunting seasons became heavily controlled, or closed altogether, and bear restoration programs began in some states. Meanwhile, the forests that had been cut and burned decades before began to grow again in many areas. As bear habitat increased, so did black bear numbers.

Beginning in the late 1980s through the start of the twenty-first century, black bear numbers increased at a rate of two percent per year continent-wide, with some states such as New Jersey and Maryland reporting a five-fold increase. Though black bears have not reclaimed all of their original range across North America, their populations have rebounded to an estimated 800,000 bears in 37 states and Canada. Additionally, more states report black bears inhabiting areas they have not roamed for almost 100 years.

Hibernation

A Hibernation Overview

Hibernators prepare for winter by locating bedding sites and, in some cases, by stashing food. Some animals (e.g., woodchucks and ground squirrels) hibernate in a deep sleep. They are considered true hibernators because their body temperatures are only slightly higher than their surroundings. These hibernators are also very difficult to awaken and may appear dead. This state of torpor lasts five to seven months. Due to their high surface-to-mass body ratio, small hibernators cool fairly quickly, so they periodically warm up by moving around, eating, and passing wastes.

Black Bear Hibernation

Although black bears are not considered true hibernators because they do not enter a state of torpor, some scientists consider them super hibernators. During hibernation, they do not drink, eat, defecate, or urinate. Unlike true hibernators, the core body temperature of black bears – the temperature of the internal organs in the chest cavity, abdominal region, and head – does not differ markedly from their normal body temperature of 100 to 101°F (37.7 – 38.3°C).

Black bears primarily hibernate to conserve energy during winter’s food shortages. To prepare for hibernation, they gorge on food in the fall. This process of eating large amounts of food, called hyperphagia, builds their reserves of brown and white fat. White fat insulates the body and is metabolized to fuel bodily processes. Bears convert the chemical energy stored in their brown fat into heat to keep them warm. While hibernating, black bears recycle the nitrogen in their urine to build new proteins. Black bears can lose up to 45 percent of their body weight during hibernation, but most of this loss is in the form of fat.

Although black bear dens can offer protection from predators and the elements, the temperature inside a bear den does not vary noticeably from outside temperatures. Black bear dens also offer a fairly safe environment for females to birth and suckle their helpless young. During hibernation, black bears may become active and briefly leave their den area. Black bears usually do not reuse their dens from year to year. Hibernation can last for up to seven months in the northern regions of North America, although black bears in the southern United States may enter their dens later and hibernate for shorter periods of time. If enough food is available in southern regions, some black bears may not hibernate at all.

Adaptations

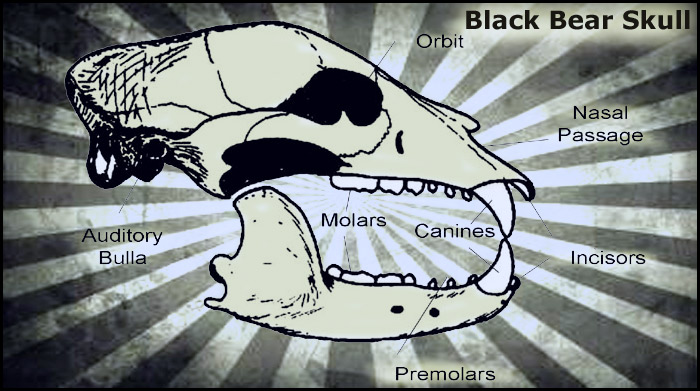

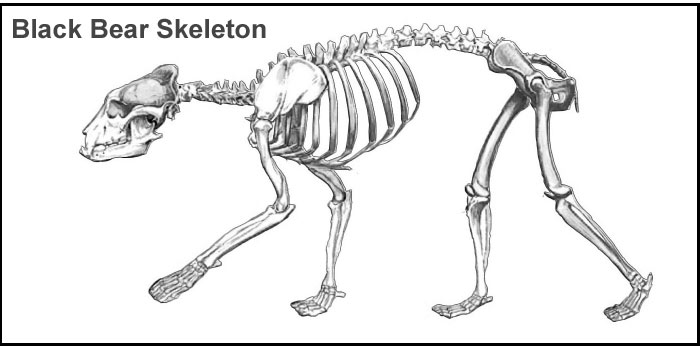

Like all animals, black bears exhibit specific adaptations that help them survive in their habitats. Black bears are scientifically classified in the order Carnivora because they have canine teeth. However, unlike other members of this order (such as wolves, foxes, and cats) black bears are not efficient predators. They lack the sharp molars and premolars of true carnivores. Their massive body structure with thick legs, enormous shoulders, and a short back, are designed for strength and power rather than for speed for catching prey. Although they can run swiftly over short distances, reaching speeds of up to 30 miles per hour, black bears quickly overheat due to their large size.

Like coyotes and raccoons, black bears function as omnivores. Plants comprise up to 95 percent of their diet. However, their digestive tracts lack caecums and rumens, organs found in herbivores such as deer. Therefore, black bears’ food moves quickly through their digestive systems. Much of the plant fiber is undigested, so fewer nutrients are removed. Black bears solve this problem by eating huge quantities of food, especially before hibernation. They also selectively forage (search for food) for easily digestible plants with concentrated nutrients (e.g., fruits and nuts). Black bears also have prehensile (detached) lips. This adaptation enables them to pluck berries from shrubs and trees.

Feet also provide clues to an animal’s lifestyle. A black bear’s long, curved claws help them climb tree trunks to reach nuts, seeds, and leaves; rip open logs and insect mounds; and overturn rocks to scavenge for insects. Like humans, they have plantigrade feet. The structure of the foot allows plantigrade species to place their entire foot on the ground during each stride; this improves balance. This broad base of support allows humans to easily walk upright. It also permits bears to stand upright briefly to improve their ability to see and hear. Bears also may stand to claw tree trunks or fence posts, or to display aggression against other bears. Plantigrade species are slower moving animals. In contrast, digitigrade species like dogs and cats walk on the entire length of their toes, with the heel raised. This allows for faster motion. Unguligrade species such as deer and horses walk on their tiptoes.

Little research is available on the extent of black bears’ sight and hearing, but evidence suggests that bears may have the keenest sense of smell in the animal world. Bears’ exceptional noses are used to locate mates, detect and avoid danger, and find food. When searching for prey, bears primarily rely on their sense of smell and hearing. A combination of smell and sight are often used to locate nuts, berries, and other plant foods.

Foraging Adaptations

Black bears have their own unique set of food-gathering adaptations. Foraging as omnivores, black bears readily eat both plant and animal matter. Although 75 to 95 percent of their diet consists of plant material, black bears lack some of the adaptations of herbivores. They cannot efficiently digest much of the plant fiber they eat.

Natural foods commonly eaten by black bears include nuts, fruits and berries, crayfish, frogs, honey, mushrooms, seeds, ants, bees, beetles, eggs, cambium (tree under bark), carrion, fish, grasses, and herbs. Black bears often locate a food source with their keen sense of smell. They also use their eyes and ears to locate food. Their curved claws and heavy muscle structure help them climb trees to feed on nuts, fruits, and leaves; rip open tree stumps in search of honey; and overturn logs to reach insects. Both claws and teeth are used to capture and eat fish.

Diet

Black bear diets vary seasonally. When they emerge from their dens in spring, black bears forage primarily on grasses and insects. They also feed on carrion (dead animal matter). They may lose weight during this time.

During late spring through late summer, bears eat mostly fruits, or soft mast. This soft mast diet may include blackberries, pokeberries, wild cherries, sassafras berries, blueberries, and other berries. They supplement their diet during the summer with higher protein insects. Through late summer and fall, black bears forage primarily on tree nuts, or hard mast. This hard mast commonly includes hickory nuts, beechnuts, hazelnuts, and a variety of acorns. The amount and type of nuts varies considerably each year by location and season. Black bears depend on acorns in many areas of the country, while beechnuts are the primary hard mast in parts of the Northeast.

These high-energy mast foods are essential to black bears in the fall. The high-fat content of nuts helps black bears build up body fat to prepare them for winter hibernation. Availability of fall foods can influence black bears’ reproductive success, habitat use, home range, movement patterns, and ultimately survival. During fall feeding, black bears may gain 100 pounds or more before going into their winter dens.

Natural food shortages can result from failure of berry and hard mast crops due to early frosts or drought, habitat loss due to development, and competition with other bears due to an increase in population. When there is a shortage in natural food sources, black bears must range farther to find the food they need to survive. By late summer and early fall, hungry bears may start to wander closer to humans in search of food. Being opportunistic feeders, they may seek out farm crops, birdseed, pet food, foods placed in compost bins, honey from managed beehives, and livestock. Young male bears driven into marginal habitats by older, dominant bears are the most likely to venture too close to humans.

Videos on American Black Bears

Quick Hibernation Ecofact

Living with Bears in Virginia

Student Resources – Books

- Flying with the Eagle, Racing the Great Bear: Stories from Native North America. Joseph Bruchac. Various Publishers; Grades 5-8.

- How Chipmunk Got His Stripes. Joseph Bruchac. Puffin Book; 2003. Grades K-3.

- Native American Animal Stories. Joseph Bruchac and Michael J. Caduto. Fulcrum Publishing; 1992. Grades 1-5.

- The Boy Who Lived with Bears: And Other Iroquois Stories. Joseph Bruchac. Parabola Books; 2003. Grades 1-4.

- The Legend of the Teddy Bear. Frank Murphy. Sleeping Bear Press; 2000. Grades K-3.

- The Legend of Sleeping Bear. Kathy-Jo Wargin. Sleeping Bear Press; 1998. Grades K-3.

Other Great Web Resources for Black Bears

- Bear Trust International

- Bears.org

- Carnivore Ecology and Conservation

- The Center for Wildlife Information’s Be Bear Aware Program

- Great Bear Foundation

- Human Bear Conflict: an international issue

- International Association for Bear Research & Management (IBA)

- National Park Service Bear Facts; The Essentials for Traveling in Bear Country:

- Servheen, C., Herrero, S. and Peyton, B. (1999) Bears: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN/SSC Bear and Polar Bear Specialist Groups, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.

- Ursus International

Related Topics

In North America, the black bear (Ursus americanus) is the most common species of bear. It is native to the continent and ranges from northern Alaska to Mexico. In fact the black bear is found in 41 of the 50 states in the U.S.A. While the brown bear is Eurasian in origin, the black bear is currently thought to have evolved in North America about two million years ago. Here is quick video clip talking about black bear hibernation. In fact, we helped with a small study with the Michigan DNR.

Life History Characteristics

Black bears are usually solitary animals whose lifestyles are dictated by their biological need to consume large quantities of food. Bears only tolerate the presence of other bears during the breeding season, when a female is with her cubs, or when bears congregate in areas with concentrated food sources such as garbage dumps and salmon streams. Adult male bears are not part of the family unit.

Reproduction

Bears reproduce at a very low rate compared to other North American land mammals. Female black bears usually become sexually mature between the ages of two and seven years. The age of first reproduction varies geographically, depending on the availability of food and the size and condition of the bears. Males (called boars) and females (called sows) may mate with more than one partner. The mating period usually occurs in June or July and lasts from two to five days. During this time, males roam extensively in search of receptive females. Implantation of the fertilized eggs in the uterine wall does not occur until the female is ready to enter the den, usually in October (in northern regions) or November (in central regions). This phenomenon is called delayed implantation. If a female does not gain enough weight before hibernation, her body may reabsorb the eggs.

Birth and Growth of Cubs

Cubs are born in the den during January or February and emerge from the den in April. Litter size can range from one to five cubs, with two-cub litters the most common. Older or heavier black bears often produce more offspring. Newborn cubs weigh seven to 11 ounces (200 to 300 grams). By six weeks of age, cubs weigh about four to seven pounds (two to three kg). Newborn cubs are altricial (helpless at birth). Their eyes are closed, and they are covered with fine, down-like fur. Because bears are mammals, the first meal they receive in life is rich milk from their mothers. Bear cubs grow rapidly because bear milk has a very high fat and protein content. Cubs nurse while they are in the den and may continue nursing through the summer.

Cubs remain with their mothers for about a year and a half. During this time, they learn fundamental skills from their mothers. These early learning experiences shape a cub’s future behavior. Throughout life, bears also learn by trial and error and by observing other bears. Eighteen months after the cubs are born, the family unit breaks up. Cubs, now called yearlings, begin searching for their own home ranges. Female yearlings usually remain within or near their mothers’ home range, but male yearlings must find territories to claim as their own. Dispersal is a difficult and dangerous time. Although black bears have few natural predators, adult male bears will kill and eat yearlings. Since dominant males occupy the best habitats, younger male bears are often pushed into marginal habitats. Frequently, marginal habitats are close to rural homes, towns, or cities. As a result, young male bears have a higher risk of mortality from vehicle collisions, hunting, and negative encounters with humans.

Mortality

Diseases rarely impact black bears. However, dental cavities are common due to their sugar-rich diet. Young or smaller bears are occasionally preyed upon by brown (grizzly) bears, wolves, bobcats, and other black bears. Once bears reach maturity at four to eight years of age, hunting, trapping, poaching, and vehicle collisions are the main causes of death. Vehicle mortality may be higher than reported because bears can sustain mortal injuries and continue to travel considerable distances from roadways. Male bears suffer higher vehicle mortality than females because of their larger home ranges, in combination with their habit of crossing and following roadways. In remote wild areas, black bears can live up to 30 years.

Behavior

Black bears are highly curious, very intelligent, mobile, and adaptable animals. They quickly learn by trial and error, adapting to new stimuli and circumstances. For example, one study indicated that bears near urban/wild land edges were active fewer hours each day, entered their dens later, remained in them for fewer days, and shifted their activities to nocturnal periods. Curious black bears will explore and learn about novel objects in their environment by manipulating them with their forepaws and by chewing. Bears can also learn from other bears; bear cubs learn many behaviors by watching their mother.

Like most animals, black bears exhibit certain behaviors that can sometimes forecast their mood or intentions. A black bear standing on its hind legs is often curious, and is trying to see or hear better. A nervous black bear may salivate excessively. A frightened black bear may run off or act defensively, giving visual and vocal cues such as swatting the ground with its paw or blowing explosively through its nostrils.

Other defensive displays by a bear may include huffing, moaning, jaw popping, or lowering its head with its ears drawn back while facing the danger. Black bears’ metabolic need to eat a year’s worth of food in seven to nine months significantly affects their behavior. Hungry black bears may roam farther than usual in search of food, sometimes beyond the normal range of the species.

Black Bear Populations

In many areas of the county, black bear populations have recovered from historic lows. Beginning in the late 1980s through the start of the 21st century, black bear numbers increased at a rate of two percent a year continent wide. Changes benefiting black bears during this time included reforestation of the landscape, black bear reintroduction programs, and regulations on hunting black bears.

Though black bears have not reclaimed all of their original range across America, they have rebounded to populations of an estimated 800,000 bears in 37 states and all Canadian Provinces. At the same time, human populations have expanded, numerically and geographically. In some areas, these two expanding populations are intersecting. In overlapping habitats, humans can often coexist with black bears. The challenge is to find a balance between the number of black bears a habitat can support, called the biological carrying capacity, and the number of bears the human community will accept, called the cultural carrying capacity.

Coexisting with Black Bears

A key factor in predicting a person’s attitudes towards black bears is his or her perception of how dangerous bears are. Familiarity fosters positive attitudes. In New York State, a 2002 mail survey indicated the majority of residents enjoyed having black bears in the state. Most survey respondents had seen a wild black bear and almost all perceived it as a positive experience. Negative attitudes towards black bears are often related to concerns for personal safety, reactions to bear damage to crops or property, and beliefs centering on real or perceived competition for game and habitat.

If you want to know how to survive a black bear attack at some point, head over to StoneAgeMan.

Human behaviors that can benefit black bear populations include habitat restoration and conservation programs, land use planning to limit habitat fragmentation, research and management programs, and wildlife education programs. Human behaviors that negatively affect black bears include feeding bears, harassing bears, land development in “bear country,” human activities that reduce natural bear food sources, and management strategies that affect other wildlife species that compete for resources (i.e. White-tailed deer).

Subspecies of Black Bear:

There are several different subspecies of black bear including the Cinnamon Bear, Glacier Bear, and Kermode Bear. The following list describes some of the accepted subspecies.

| Ursus americanus altifrontalis | This subspecies lives in the Pacific NW from central BC to northern Cal and inland to Northern Idaho. |

| Ursus americanus amblyceps | Found in CO, NM, AZ, west TX, southeaster Utah and northern Mexico. |

| Ursus americanus americanus | This subspecies is widespread from eastern MT to the east coast. Its found as far north as Alaska and south to TX. |

| Ursus americanus californiensis | This California bear is found in the mountains from southern Oregon to southern CA. |

| Ursus americanus carlottae | The Queen Charlotte Black Bear is found on the Queen Charlotte Islands and the Alaska mainland. |

| Ursus americanus cinnamomum | The Cinammon Bear is found in ID, western MT, WY, eastern WA, northeastern UT and OR. |

| Ursus americanus emmonsii | Found in southeastern AK |

| Ursus americanus eremicus | Lives in northeastern Mexico |

| Ursus americanus floridanus | In the south this bear ranges from FL, southern Georgia to Alabama. |

| Ursus americanus hamiltoni | This bear lives on the island of Newfoundland |

| Ursus americanus kermodei | The Kermode Bear lives on the central coast of British Columbia |

| Ursus americanus luteolus | Found natively in eastern TX, LA, and southern MS |

| Ursus americanus machetes | Native to north-central Mexico |

| Ursus americanus perniger | Native to the Kenai Pennisula, AK |

| Ursus americanus pugnax | Found on the Alexander Archipelago in AK |

| Ursus americanus vancouveri |

Bear History

Before Columbus

When humans first entered North America some 15,000 years ago, bears inhabited every corner of the continent. The grizzly bear thrived in all western states, ranging as far south as Mexico and as far north as the tip of Alaska. Related to the grizzly bear, but with certain behavioral, morphological, and physiological differences, the smaller black bear roamed North America from the Atlantic to the Pacific and from Mexico to the northern edges of the continent. To Native Americans, the black bear provided a valuable source of thick hides for clothing and shelter, rich meat, and sweet fat. The unique traits of the bear itself provided the essence of their legends. Native Americans pass on these legends through an oral tradition called storytelling. These stories teach the young, pass on a tribe’s rituals and beliefs, safeguard history, and entertain the listeners. Some stories describe how an animal acquired a physical characteristic while others tell about the animal’s relationships with people or other wildlife.

Pioneers Arrive

Early American settlers found black bears in abundance when they arrived, but the bears represented more than a food source to early pioneers. Settlers brought with them European perceptions and behaviors; wilderness was viewed as threatening, as were the wild animals living in it. Bounties placed on predators became common, such as the one-penny bounty for a dead wolf in Massachusetts Bay Colony. To the settlers, bears posed threats to their families, livestock, crops, and future. This attitude surfaced in popular nature books of that time which showed animals such as bears attacking hunters or eagles flying off with children. Settlers did not just kill bears with their guns. Cutting, burning and clearing changed the wooded lands into open farm fields and pastures. As the wave of humans expanded, black bears lost much of their native habitat, restricting their populations to some of the more mountainous, swampy, and rugged regions of North America.

Conservation Awakens

The few black bears that remained in the mid 1800s came under the pressure of unregulated market hunting for their hides, meat, and fat. Due to their low reproductive rate, bears recover more slowly from population losses than other North American mammals. By 1900, black bear numbers dwindled in many areas of the country, nearing the point of extinction. Eventually, America began to realize the importance of wildlife management, including the plight of the black bear. By the mid-1900s, hunting seasons became heavily controlled, or closed altogether, and bear restoration programs began in some states. Meanwhile, the forests that had been cut and burned decades before began to grow again in many areas. As bear habitat increased, so did black bear numbers.

Beginning in the late 1980s through the start of the twenty-first century, black bear numbers increased at a rate of two percent per year continent-wide, with some states such as New Jersey and Maryland reporting a five-fold increase. Though black bears have not reclaimed all of their original range across North America, their populations have rebounded to an estimated 800,000 bears in 37 states and Canada. Additionally, more states report black bears inhabiting areas they have not roamed for almost 100 years.

Hibernation

A Hibernation Overview

Hibernators prepare for winter by locating bedding sites and, in some cases, by stashing food. Some animals (e.g., woodchucks and ground squirrels) hibernate in a deep sleep. They are considered true hibernators because their body temperatures are only slightly higher than their surroundings. These hibernators are also very difficult to awaken and may appear dead. This state of torpor lasts five to seven months. Due to their high surface-to-mass body ratio, small hibernators cool fairly quickly, so they periodically warm up by moving around, eating, and passing wastes.

Black Bear Hibernation

Although black bears are not considered true hibernators because they do not enter a state of torpor, some scientists consider them super hibernators. During hibernation, they do not drink, eat, defecate, or urinate. Unlike true hibernators, the core body temperature of black bears – the temperature of the internal organs in the chest cavity, abdominal region, and head – does not differ markedly from their normal body temperature of 100 to 101°F (37.7 – 38.3°C).

Black bears primarily hibernate to conserve energy during winter’s food shortages. To prepare for hibernation, they gorge on food in the fall. This process of eating large amounts of food, called hyperphagia, builds their reserves of brown and white fat. White fat insulates the body and is metabolized to fuel bodily processes. Bears convert the chemical energy stored in their brown fat into heat to keep them warm. While hibernating, black bears recycle the nitrogen in their urine to build new proteins. Black bears can lose up to 45 percent of their body weight during hibernation, but most of this loss is in the form of fat.

Although black bear dens can offer protection from predators and the elements, the temperature inside a bear den does not vary noticeably from outside temperatures. Black bear dens also offer a fairly safe environment for females to birth and suckle their helpless young. During hibernation, black bears may become active and briefly leave their den area. Black bears usually do not reuse their dens from year to year. Hibernation can last for up to seven months in the northern regions of North America, although black bears in the southern United States may enter their dens later and hibernate for shorter periods of time. If enough food is available in southern regions, some black bears may not hibernate at all.

Adaptations

Like all animals, black bears exhibit specific adaptations that help them survive in their habitats. Black bears are scientifically classified in the order Carnivora because they have canine teeth. However, unlike other members of this order (such as wolves, foxes, and cats) black bears are not efficient predators. They lack the sharp molars and premolars of true carnivores. Their massive body structure with thick legs, enormous shoulders, and a short back, are designed for strength and power rather than for speed for catching prey. Although they can run swiftly over short distances, reaching speeds of up to 30 miles per hour, black bears quickly overheat due to their large size.

Like coyotes and raccoons, black bears function as omnivores. Plants comprise up to 95 percent of their diet. However, their digestive tracts lack caecums and rumens, organs found in herbivores such as deer. Therefore, black bears’ food moves quickly through their digestive systems. Much of the plant fiber is undigested, so fewer nutrients are removed. Black bears solve this problem by eating huge quantities of food, especially before hibernation. They also selectively forage (search for food) for easily digestible plants with concentrated nutrients (e.g., fruits and nuts). Black bears also have prehensile (detached) lips. This adaptation enables them to pluck berries from shrubs and trees.

Feet also provide clues to an animal’s lifestyle. A black bear’s long, curved claws help them climb tree trunks to reach nuts, seeds, and leaves; rip open logs and insect mounds; and overturn rocks to scavenge for insects. Like humans, they have plantigrade feet. The structure of the foot allows plantigrade species to place their entire foot on the ground during each stride; this improves balance. This broad base of support allows humans to easily walk upright. It also permits bears to stand upright briefly to improve their ability to see and hear. Bears also may stand to claw tree trunks or fence posts, or to display aggression against other bears. Plantigrade species are slower moving animals. In contrast, digitigrade species like dogs and cats walk on the entire length of their toes, with the heel raised. This allows for faster motion. Unguligrade species such as deer and horses walk on their tiptoes.

Little research is available on the extent of black bears’ sight and hearing, but evidence suggests that bears may have the keenest sense of smell in the animal world. Bears’ exceptional noses are used to locate mates, detect and avoid danger, and find food. When searching for prey, bears primarily rely on their sense of smell and hearing. A combination of smell and sight are often used to locate nuts, berries, and other plant foods.

Foraging Adaptations

Black bears have their own unique set of food-gathering adaptations. Foraging as omnivores, black bears readily eat both plant and animal matter. Although 75 to 95 percent of their diet consists of plant material, black bears lack some of the adaptations of herbivores. They cannot efficiently digest much of the plant fiber they eat.

Natural foods commonly eaten by black bears include nuts, fruits and berries, crayfish, frogs, honey, mushrooms, seeds, ants, bees, beetles, eggs, cambium (tree under bark), carrion, fish, grasses, and herbs. Black bears often locate a food source with their keen sense of smell. They also use their eyes and ears to locate food. Their curved claws and heavy muscle structure help them climb trees to feed on nuts, fruits, and leaves; rip open tree stumps in search of honey; and overturn logs to reach insects. Both claws and teeth are used to capture and eat fish.

Diet

Black bear diets vary seasonally. When they emerge from their dens in spring, black bears forage primarily on grasses and insects. They also feed on carrion (dead animal matter). They may lose weight during this time.

During late spring through late summer, bears eat mostly fruits, or soft mast. This soft mast diet may include blackberries, pokeberries, wild cherries, sassafras berries, blueberries, and other berries. They supplement their diet during the summer with higher protein insects. Through late summer and fall, black bears forage primarily on tree nuts, or hard mast. This hard mast commonly includes hickory nuts, beechnuts, hazelnuts, and a variety of acorns. The amount and type of nuts varies considerably each year by location and season. Black bears depend on acorns in many areas of the country, while beechnuts are the primary hard mast in parts of the Northeast.

These high-energy mast foods are essential to black bears in the fall. The high-fat content of nuts helps black bears build up body fat to prepare them for winter hibernation. Availability of fall foods can influence black bears’ reproductive success, habitat use, home range, movement patterns, and ultimately survival. During fall feeding, black bears may gain 100 pounds or more before going into their winter dens.

Natural food shortages can result from failure of berry and hard mast crops due to early frosts or drought, habitat loss due to development, and competition with other bears due to an increase in population. When there is a shortage in natural food sources, black bears must range farther to find the food they need to survive. By late summer and early fall, hungry bears may start to wander closer to humans in search of food. Being opportunistic feeders, they may seek out farm crops, birdseed, pet food, foods placed in compost bins, honey from managed beehives, and livestock. Young male bears driven into marginal habitats by older, dominant bears are the most likely to venture too close to humans.

Videos on American Black Bears

Quick Hibernation Ecofact

Living with Bears in Virginia

Student Resources – Books

- Flying with the Eagle, Racing the Great Bear: Stories from Native North America. Joseph Bruchac. Various Publishers; Grades 5-8.

- How Chipmunk Got His Stripes. Joseph Bruchac. Puffin Book; 2003. Grades K-3.

- Native American Animal Stories. Joseph Bruchac and Michael J. Caduto. Fulcrum Publishing; 1992. Grades 1-5.

- The Boy Who Lived with Bears: And Other Iroquois Stories. Joseph Bruchac. Parabola Books; 2003. Grades 1-4.

- The Legend of the Teddy Bear. Frank Murphy. Sleeping Bear Press; 2000. Grades K-3.

- The Legend of Sleeping Bear. Kathy-Jo Wargin. Sleeping Bear Press; 1998. Grades K-3.

Other Great Web Resources for Black Bears

- Bear Trust International

- Bears.org

- Carnivore Ecology and Conservation

- The Center for Wildlife Information’s Be Bear Aware Program

- Great Bear Foundation

- Human Bear Conflict: an international issue

- International Association for Bear Research & Management (IBA)

- National Park Service Bear Facts; The Essentials for Traveling in Bear Country:

- Servheen, C., Herrero, S. and Peyton, B. (1999) Bears: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN/SSC Bear and Polar Bear Specialist Groups, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.

- Ursus International