The Emerald Ash Borer

Agrilus planipennis

The emerald ash borer is known by entomologists by its acronym: EAB. If you’re an insect aficionado or a tree lover, you likely already know this name. For the rest of you, it’s a name you will know soon enough. It is the cause of arguably the most catastrophic tree death event in the history of North America.

We just finished a 3 month deep dive interviewing EAB experts from around the country and compiling a list of things you need to know about EAB so we can all help scientists mitigate this problem. First, let’s get you up to speed with this short (and may I say, fun) video.

Biology of the Emerald Ash Borer

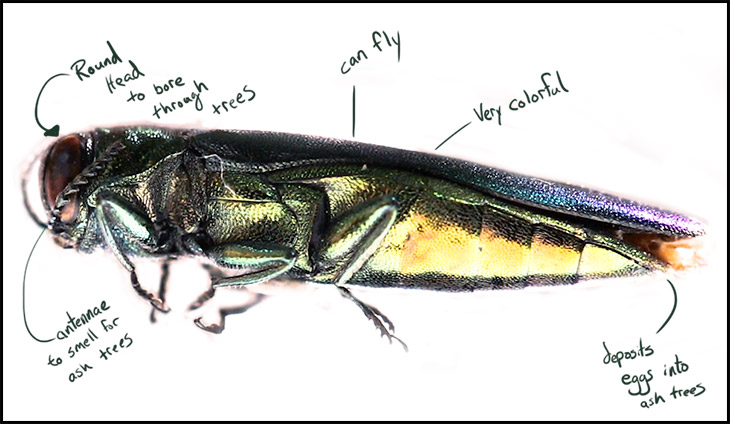

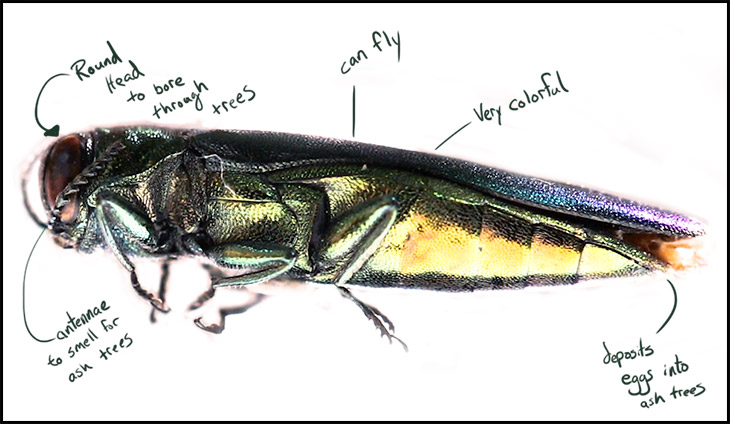

The emerald ash borer is a small wood-boring beetle in the family Buprestidae. While there are thousands of wood boring beetles in the world, most cause no problems at all. They add life to the forest and actually perform helpful biological processes for us. This is not the case for this invasive insect. That is in large part because it was introduced to North America where it has no natural predators and its food (ash trees) has no natural defenses. Below is a snapshot of an adult beetle.

This is the adult phase of the beetle that can fly around, mate and lay eggs on ash trees. From these eggs, the larvae hatch. It’s this life stage that causes the real problems. It feeds just under the tree bark on the phloem tissue. Just look at the growing size of these feeding trails on this (now dead) ash tree trunk.

As these feeding trails coalesce, it completely cuts off the tree’s ability to transport nutrients to other parts of the tree and it dies.

When did EAB arrive in North America?

The answer to this is tricky because nobody saw an infected shipment en-route to the US. However, in 2002 EAB was detected in Michigan in ash trees near Detroit. Likely, these insects caught a ride on some shipment into Detroit in the year or two prior. They jumped ship from packaging material and found a tasty ash tree to lay their eggs. The infestation we see now has spread entirely from this small introduction at the turn of the decade.

Now, we are looking at an invasion of 33 US states and several territories in Canada.

Where Did Emerald Ash Borers Come From?

The Emerald Ash Borer (EAB) is actually native to Asia including China, Korea, and Japan. In its native land it does feed on native asian ash trees. However, the ash trees there seem more resistant to this beetle. In Asia, there are also several predators that have co-evolved with these beetles. This acts to keep the population size down and minimize its effect on the ash trees there.

How Much Has EAB Spread Now?

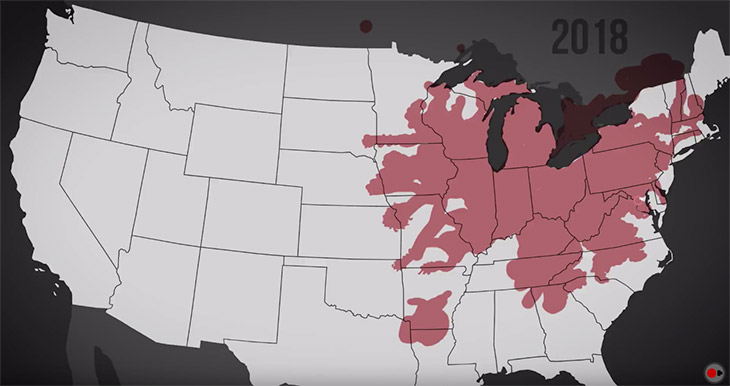

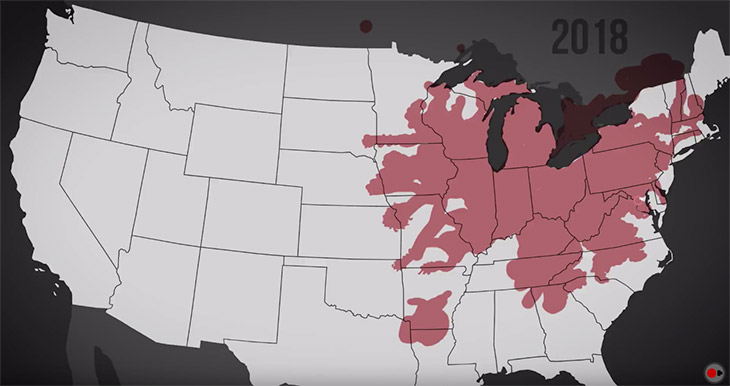

This map shows the current range of the emerald ash borer as of the making of this video.

The range and spread of the beetle is updated every month by entomologists and can be found via this emerald ash borer monitoring site.

How can you help?

Although the invasion is well underway and quickly covering the east coast of the US, there is still hope. We can learn from the destruction that has already occurred and help mitigate the damage in areas that it is spreading.

Here’s what you can do:

Identify An Ash Tree

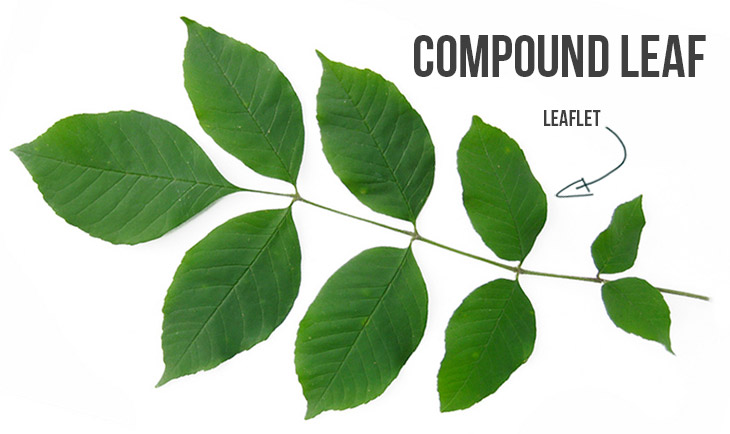

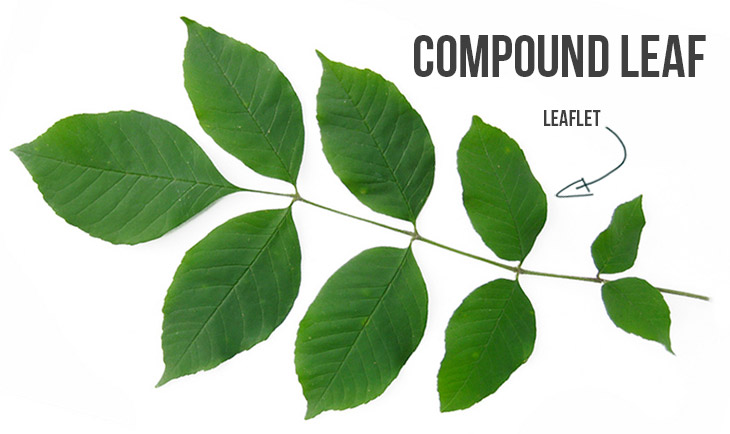

Ash trees are easy to identify and they’re more common that you might think. This is the leaf of an ash tree.

Notice that each leaf has several leaflets that come off the main leaf stem. The main trees that look similar to ashes in the US are hickories. If you nee more help identifying your tree, I’m going to point you to this resource.

What If My Tree Dies From the Emerald Ash Borer?

If a tree dies from the emerald ash borer it can still act as a food source for the beetle. That is a huge problem for the other trees in the area. First, let someone know that your tree has died – especially if you are in an area that is not known to have EAB. Secondly, to prevent the continued spread of this bug in your area, these dead trees should be chopped up and destroyed.

Treat Hi-Value Ash Trees with Insecticide to Kill EAB

If you find a tree that shows signs of dying or EAB has been found in the vicinity, you can treat trees to help save them. Treatment is only effective if done early or before infestation has progressed too far. In the later stages of attack the insecticide may not work to save the tree. I went out with Dr. Andrew Loyd, an arborist with Bartlett tree research laboratory in Charlotte NC to help give me a better picture of what kind of insecticide is being used and how it is applied.

Diversify Your Trees

We never know what the next invasive pest or pathogen is going to be. The key to protecting our cities and forests is working to increase diversity. This diversity will both help slow the spread of pathogens and it will allow us to have some resilience when something does kill a particular species of tree.

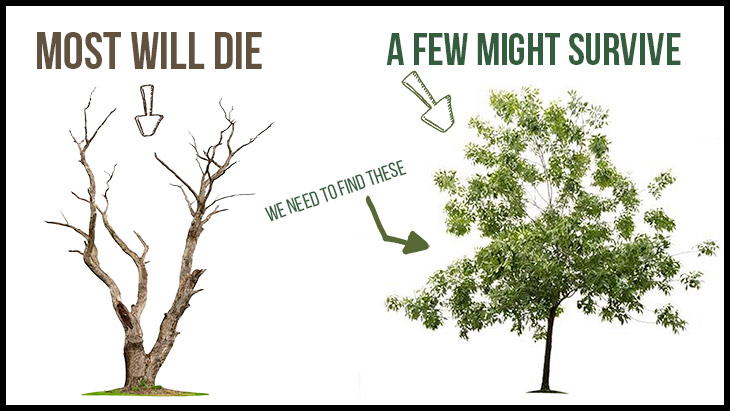

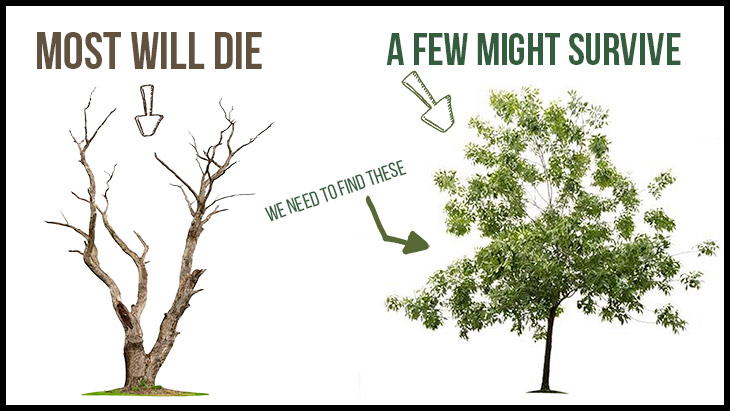

Find Insect-Resistant Trees

This infestation will likely kill 99.99+ percent of the ash trees in the country. Yet, amidst this destruction there will be survivors. Scientists need to know about these trees that have this magical set of genes that allow them to resist the emerald ash borer. If you find an ash tree that should have died, but has not, let someone know. It may be the beginning of the next generation of ash in America!

Don’t Move Firewood

It’s true, the emerald ash borer adults can fly. That means it will move without out help. But, it won’t fly more than a mile or two every year. That slow spread of this insect means it’ll take decades to centuries for it to naturally cross the country. That spread is unfortunately amplified when people toss infested wood into their vehicles and carry them on highways for hundreds of miles. For example, EAB just showed up in Denver Colorado. It didn’t fly there. Someone brought it in infested firewood! It’s an easy thing you can do to help. Stop moving firewood!

More Great Resources on the Emerald Ash Borer

- Simple Steps to Stopping the Emerald Ash borer (by Hugh Markey)

- Emerald Ash Borer Invasion of North America: History, Biology, Ecology, Impacts, and Management

- Emerald Ash Borer Information Network

Special Help with This Project

This project was a collaboration between a ton of different people and groups. We wanted to point out everyone who helped us create this resource here.

- Jeff Eickwort at the Florida Forest Service helped us find financial resources to make this film to help Florida residents understand what is coming and have a set of simple tools to put into action to help slow its spread as it approaches.

- Dr. Jiri Hulcr is the forest entomologist at the University of Florida. His guidance and expertise in finding various experts for the film was the only way this film was made. He also provided his skilled storytelling ability throughout the narrative. Without him, the project wouldn’t have gotten off the ground. Also special thanks to Dr. Andrea Lucky and the Hulcr family for being tour guides as we drove around town getting all this footage.

- Dr. Lynne Rieske-Kinney is the forest entomologist at the University of Kentucky. She helped organize the amazing crew on the ground in Lexington where all the trees were falling. Thank you to all of the amazing crew on the ground there for helping us get some stellar footage of tree-falls.

- Dr. Jason Smith is a forest pathologist at the University of Florida / IFAS who gave us a ton of information about solutions in ash tree health moving forward.

- The Hulcr lab at the University, had a ton of fantastic people who helped get macro shots of these beetles. In particular, Dr. Andrew Johnson spent two days with us in the lab getting these macro shots.

- Dr. Andrew Loyd at Bartlett Tree Research Laboratories gave us a detailed walkthrough of treatment solutions for ash trees.

- Haley Chamberlain and Jonas Stenstrom served as the photographers and filmmakers on this project. It was directed by Rob Nelson.

- Our patrons here helped us fund the creative outreach projects that linked to this, such as the how-to-photography video, the gimbal video and the ash tree treatment videos. Those videos help us do so much more with projects like this. A special thanks goes to Tobias Haase, Dennis Horn, Medesthai, and Johanna van de Woestijne for their extra support.

Related Topics

The emerald ash borer is known by entomologists by its acronym: EAB. If you’re an insect aficionado or a tree lover, you likely already know this name. For the rest of you, it’s a name you will know soon enough. It is the cause of arguably the most catastrophic tree death event in the history of North America.

We just finished a 3 month deep dive interviewing EAB experts from around the country and compiling a list of things you need to know about EAB so we can all help scientists mitigate this problem. First, let’s get you up to speed with this short (and may I say, fun) video.

Biology of the Emerald Ash Borer

The emerald ash borer is a small wood-boring beetle in the family Buprestidae. While there are thousands of wood boring beetles in the world, most cause no problems at all. They add life to the forest and actually perform helpful biological processes for us. This is not the case for this invasive insect. That is in large part because it was introduced to North America where it has no natural predators and its food (ash trees) has no natural defenses. Below is a snapshot of an adult beetle.

This is the adult phase of the beetle that can fly around, mate and lay eggs on ash trees. From these eggs, the larvae hatch. It’s this life stage that causes the real problems. It feeds just under the tree bark on the phloem tissue. Just look at the growing size of these feeding trails on this (now dead) ash tree trunk.

As these feeding trails coalesce, it completely cuts off the tree’s ability to transport nutrients to other parts of the tree and it dies.

When did EAB arrive in North America?

The answer to this is tricky because nobody saw an infected shipment en-route to the US. However, in 2002 EAB was detected in Michigan in ash trees near Detroit. Likely, these insects caught a ride on some shipment into Detroit in the year or two prior. They jumped ship from packaging material and found a tasty ash tree to lay their eggs. The infestation we see now has spread entirely from this small introduction at the turn of the decade.

Now, we are looking at an invasion of 33 US states and several territories in Canada.

Where Did Emerald Ash Borers Come From?

The Emerald Ash Borer (EAB) is actually native to Asia including China, Korea, and Japan. In its native land it does feed on native asian ash trees. However, the ash trees there seem more resistant to this beetle. In Asia, there are also several predators that have co-evolved with these beetles. This acts to keep the population size down and minimize its effect on the ash trees there.

How Much Has EAB Spread Now?

This map shows the current range of the emerald ash borer as of the making of this video.

The range and spread of the beetle is updated every month by entomologists and can be found via this emerald ash borer monitoring site.

How can you help?

Although the invasion is well underway and quickly covering the east coast of the US, there is still hope. We can learn from the destruction that has already occurred and help mitigate the damage in areas that it is spreading.

Here’s what you can do:

Identify An Ash Tree

Ash trees are easy to identify and they’re more common that you might think. This is the leaf of an ash tree.

Notice that each leaf has several leaflets that come off the main leaf stem. The main trees that look similar to ashes in the US are hickories. If you nee more help identifying your tree, I’m going to point you to this resource.

What If My Tree Dies From the Emerald Ash Borer?

If a tree dies from the emerald ash borer it can still act as a food source for the beetle. That is a huge problem for the other trees in the area. First, let someone know that your tree has died – especially if you are in an area that is not known to have EAB. Secondly, to prevent the continued spread of this bug in your area, these dead trees should be chopped up and destroyed.

Treat Hi-Value Ash Trees with Insecticide to Kill EAB

If you find a tree that shows signs of dying or EAB has been found in the vicinity, you can treat trees to help save them. Treatment is only effective if done early or before infestation has progressed too far. In the later stages of attack the insecticide may not work to save the tree. I went out with Dr. Andrew Loyd, an arborist with Bartlett tree research laboratory in Charlotte NC to help give me a better picture of what kind of insecticide is being used and how it is applied.

Diversify Your Trees

We never know what the next invasive pest or pathogen is going to be. The key to protecting our cities and forests is working to increase diversity. This diversity will both help slow the spread of pathogens and it will allow us to have some resilience when something does kill a particular species of tree.

Find Insect-Resistant Trees

This infestation will likely kill 99.99+ percent of the ash trees in the country. Yet, amidst this destruction there will be survivors. Scientists need to know about these trees that have this magical set of genes that allow them to resist the emerald ash borer. If you find an ash tree that should have died, but has not, let someone know. It may be the beginning of the next generation of ash in America!

Don’t Move Firewood

It’s true, the emerald ash borer adults can fly. That means it will move without out help. But, it won’t fly more than a mile or two every year. That slow spread of this insect means it’ll take decades to centuries for it to naturally cross the country. That spread is unfortunately amplified when people toss infested wood into their vehicles and carry them on highways for hundreds of miles. For example, EAB just showed up in Denver Colorado. It didn’t fly there. Someone brought it in infested firewood! It’s an easy thing you can do to help. Stop moving firewood!

More Great Resources on the Emerald Ash Borer

- Simple Steps to Stopping the Emerald Ash borer (by Hugh Markey)

- Emerald Ash Borer Invasion of North America: History, Biology, Ecology, Impacts, and Management

- Emerald Ash Borer Information Network

Special Help with This Project

This project was a collaboration between a ton of different people and groups. We wanted to point out everyone who helped us create this resource here.

- Jeff Eickwort at the Florida Forest Service helped us find financial resources to make this film to help Florida residents understand what is coming and have a set of simple tools to put into action to help slow its spread as it approaches.

- Dr. Jiri Hulcr is the forest entomologist at the University of Florida. His guidance and expertise in finding various experts for the film was the only way this film was made. He also provided his skilled storytelling ability throughout the narrative. Without him, the project wouldn’t have gotten off the ground. Also special thanks to Dr. Andrea Lucky and the Hulcr family for being tour guides as we drove around town getting all this footage.

- Dr. Lynne Rieske-Kinney is the forest entomologist at the University of Kentucky. She helped organize the amazing crew on the ground in Lexington where all the trees were falling. Thank you to all of the amazing crew on the ground there for helping us get some stellar footage of tree-falls.

- Dr. Jason Smith is a forest pathologist at the University of Florida / IFAS who gave us a ton of information about solutions in ash tree health moving forward.

- The Hulcr lab at the University, had a ton of fantastic people who helped get macro shots of these beetles. In particular, Dr. Andrew Johnson spent two days with us in the lab getting these macro shots.

- Dr. Andrew Loyd at Bartlett Tree Research Laboratories gave us a detailed walkthrough of treatment solutions for ash trees.

- Haley Chamberlain and Jonas Stenstrom served as the photographers and filmmakers on this project. It was directed by Rob Nelson.

- Our patrons here helped us fund the creative outreach projects that linked to this, such as the how-to-photography video, the gimbal video and the ash tree treatment videos. Those videos help us do so much more with projects like this. A special thanks goes to Tobias Haase, Dennis Horn, Medesthai, and Johanna van de Woestijne for their extra support.