Finally, you’ve got your hands on the camera case and you’re almost ready to head to the shoot location. Admittedly, this can be one of the more exciting parts of filmmaking – production. It’s also called field production, the shoot, location shooting, or filming. It’s the pivotal process where you capture the key visual and audio elements of your film on your camera. Depending on the scope of your film, it may be as simple as a one-hour shoot at some science or wildlife site to as complex as months of traveling, shooting, and interviewing at multiple locations around the world.

Camera

Now that you know where you’re headed (your logistics plan) and what’s on your shoot list, (your shoot list made from other lists) let’s move on next to that video camera of yours. We’ll assume that you already have the best one you can get your hands on either by buying it, borrowing or renting one. Or maybe you’ve contracted with or sweet-talked some cameraperson who has his or her own. Even though you could be shooting one of those gritty cell phone videos, let’s assume you have a camera with professional settings.

I think the CAMERA section could use some work. First, I’m guessing that most people that want to make films are most interested in the cameras, yet know very little about what they need to look for. All we have are two sections … one on HD/SD (which already seems old – I say we have a few lines about how everything is HD and move on … same with tapeless videos). There are a lot of other things that people might need to know about the camera though. Plus, I think if we include the specific cameras, it’ll sound irrelevant soon. In fact, it already sounds very 2007. Here is a short list of things that could use some describing:

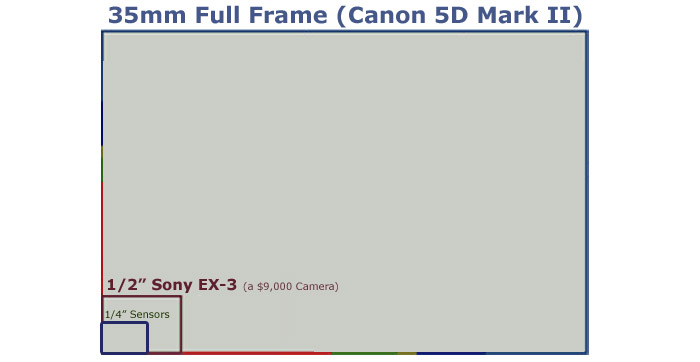

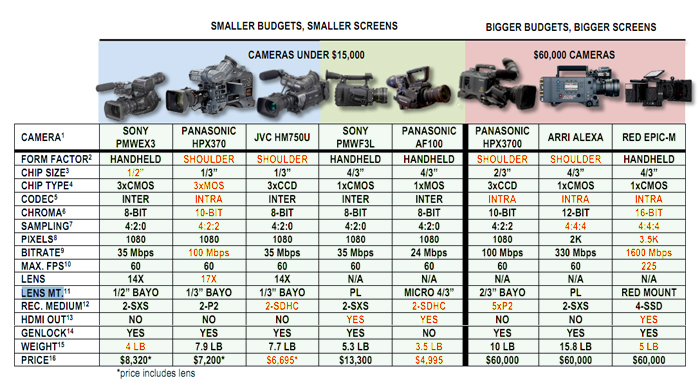

Chip Size (What does this mean when someone reads this)

Chip Type (CCD’s CMOS … etc)

Codec (There are a lot of codecs … what do they mean)

Chroma (The measure of the shades of color a camera pics up …)

Sampling (Such as 4:4:4 or 4:2:0 or 4:0:0 … and what that means)

Pixels (This of course is the resolution. But HD isn’t just 720×1080 … there is 2K resolution, 3.5K, 6K! Whats the difference).

Bitrate: Why does this mater

Max Frame Rate: Such as overcranking ability: 60FPS, 1,000 FPS…

Lens Mounts: Why would you want to switch lenses

Recording medium: P2 cards, SDHC cards, HDCAM-SR, etc.

Genlock: What is it and why would you use it.

Also it might be nice to touch on:

Whitebalance,

Gain

Focus tips

timecode

Plus, this seems like a great section to include Camera Composition tips, like types of shots and the rule of thirds.

HD or SD? – The transition from SD (standard definition, 720 lines of vertical resolution) to HD (high definition 1080 lines) happened quickly on the heels of innovative digital technology. Almost overnight tape cameras in SD, Beta SP and DVC Pro formats were out and tapeless HD was in, giving producers unprecedented image quality for a fraction of the cost of a Beta SP camera that was an enduring flagship format for such a long time.

Your camera of choice depends on a great many things such as your budget, your intended end product and the ways you might want to deliver your film to your target audiences. Nonetheless, logic says to record on the highest quality camera and format possible. The HD camera market changes so quickly and the selection is so daunting, we’ll simply suggest doing your camera research in earnest to find the best fit for your project. However, we’ll also tell you about the cameras we’ve used for hundreds of productions and what we feel are some of their performance advantages.

Tape or Tapeless? – Early on we got some Panasonic P2 cameras. The first ones were amazing things at the time that recorded directly to internal P2 cards or to MiniDV tape (SD format) on a tape drive in the camera. Though it sounded like a cool combination of features, in years of shooting we only recorded one SD tape. Panasonic must have gotten similar feedback from others as their next generations of HD P2 cameras dropped the secondary tape option altogether. Despite the insecurities of some of the more “seasoned” camerapersons of not being able to record to a tape that they could hold in their hands, everyone soon agreed that tapeless recording was the only way to go. The old days of shooting to tape, reviewing and logging tapes, cataloging tapes, making capture lists of tapes, digitizing tapes into movie files to hard drives before you could edit, are now a drudgery of the past. Now it’s simply a matter of logging and transferring your movies directly from the camera’s digital storage to a hard drive that has connectivity to allow HD data playback on your editing system.

As HD cameras get smaller and lighter, they offer increased shooting versatility and most offer various recording format options. Depending on your needs, consider cameras that will also give you 4-channel audio options, with XLR inputs for channels 1 and 2, plus the standard smattering of other professional features. Another consideration is if a camera has an available zoom-through wide-angle lenses that can offer a fun POV perspective for tight interactive shots. But before you dive headlong into getting a camera, consider the limitations of the zoom lens relative to what you’re going to be shooting. Many cameras work fine for shooting general scenes and interviews. Some however fall short on the lens power, which might not be the ideal choice if you intend on shooting distant wildlife.

One of the greatest breakthroughs since the switch to digital recording media for wildlife filmmakers is that of the digital SLR cameras, often called DSLRs or HDSLRs. We’re talking about the wide range of high end, inter-changeable lens still cameras that also shoot HD video. These cameras are affordable for the wildlife and science filmmaker and they take amazing video. However, it’s important to remember that these cameras are designed to be still cameras. They just happen to take amazing video as well. To make a film with a DSLR camera, there are a few hoops you’ll have to jump through. Don’t treat this overview as the definitive guide to DSLR filmmaking though. It’s simply intended to give some of the basics, and point you in the right direction if you want to take this path in your science filmmaking. We’ll offer some more advice on HDSLR filmmaking later on in the book.

Don’t forget those little cameras that offer the versatility and ease of shooting that some of the larger ones can’t. That’s why we also shoot on some of the little hand-held HD cameras. We’ve strapped these little palm-sized video cameras to kayaks, bikes, cable dollies, roller coasters, and just about anything that moves. And unlike the bigger P2 cameras, when using them for underwater shots in the ocean, it doesn’t cost nearly as much to replace if your camera ends up in Davey Jones’ locker. For instance, one new P2 camera lasted only one day before it got accidently soaked with saltwater. Now it’s a fun yet admittedly expensive prop camera that we can drop into the drink or mud without worry. We’ve also used the mini Go Pro HD video camera that even comes with its own waterproof housing. You can strap that little camera on just about anything, including surfboards, skis, cats, dogs and skydiving helmets. But before you begin strapping cameras to anything, let’s take a moment to go over your “before departure checklist”.

Pre-shoot Checklist

Whether you make yet another list or commit it all to memory, you should check some more important things before you load your camera gear and head to your shoot location. We typically check this stuff off our pre-shoot list the evening before a shoot or embarking on an extended production trip. Forgetting one key item can delay or mess up a shoot. And you sure don’t want to risk missing a rare opportunity that can often happen during wildlife and science shoots. So here are the basics of your pre-shoot prep list:

• Batteries – Have plenty and make sure they’re fully charged. Also have a backup plan to recharge them again or work from direct power at your shoot location. If you’re shooting for hours in a remote location such as an acacia tree overlooking an active lion kill in the Serengeti, consider a hefty extended-life battery that fits your camera.

• Clear camera memory – Assuming that you’re shooting on a tapeless camera, double-check to be sure that you’ve transferred the existing footage on your camera’s storage (P2 cards or similar storage), before you clear the memory in your camera. This is an unnerving process the first dozen or so times as the camera is essentially asking you, “are you sure you want to totally delete all this irreplaceable footage from your camera? Because if you do by mistake, you’ll feel like total crap and the rest of the production team will want to tar and feather you?” So, yes, take the time to make sure it’s been safely transferred on a hard drive or storage device.

• As a precaution, check your recording settings too. In case you show up on location just as the manatees are mating, you don’t want to record in some previously set time-lapse or slow motion mode. If it’s a multi-camera shoot, make sure (if that’s your plan) that all the cameras are set with the same recording parameters. That could save you tons of corrections later in post production.

• Lens cloth – As small as it seems, having a quality lens cloth (and a backup) is a biggie on your checklist. Few things will irritate you or your editor more than working with what should have been quality footage that was shot through a dirty lens.

• Audio gear – If you’re using wireless or shotgun audio systems on your planned shoot, make sure their batteries, cables, and settings are all set to go.

• Tripods, dollies, cranes, steady-cams, lighting – Depending on your shoot, arrange and make sure that your other camera related gear such as support systems and lighting are in working order and ready for your big shoot.

Location Check

Finally, you’ve arrived at location and though it’ okay to feel the excitement in the air, now’s the time to act like the pro that you’re quickly becoming by taking a few moments to check your shoot location and take care of any necessary business. Because each shoot is unique with its own variables, we’ll simply go over a few of the basics in chronological order that you can adapt depending on your shoot locations.

The first thing we do is meet with the people involved in our shoot and secure talent and location releases. Waiting until “later” is often an invitation to trouble happening later in the production process. The pitfalls of waiting include; on-camera people leaving early, you get distracted with B Roll afterwards, or someone suddenly has second thoughts about how they looked or sounded on camera and want to “think it over” before they sign the release. We’ll spare you the horror stories and suffice it to say that neglecting the business of getting your releases before the shoot could jeopardize the final editing or distribution of your film later on. Getting your releases signed is also a good way to break the ice with people by starting conversations about what’s going to happen during the shoot. Plus it shows that you’re a professional. We’ve even offered you some “boilerplate” talent and location releases in the resources section of this book. Feel free to edit them for your film or production company.

Getting acquainted with the person in charge of the shoot location, the expert to be interviewed, or others involved in your shoot to help establish clearer communication for when the camera begins to roll. This is also a good time to tap into the talent and resources of the people you’re working with. More often than not, the person in charge of the location has some helpful ideas on where to shoot scenes, what props might be available and other helpful information about the logistics of the shoot. We’ve shot in hundreds of locations from science labs to industrial facilities and the people in charge have revealed hidden gems of places or items to shoot that helped make our films sing with science. And don’t be shy about asking if they have or know of other sources of video about the location or topic that might available for support footage. This is also your time to request a tour so you can become familiar with your shooting environments. In a perfect world, you or one of your production team have already scouted the location beforehand and have a good idea of where and how to conduct the shoot. However, in reality you’ll often find yourself on a distant or restricted location without the luxury of a pre-shoot scouting trip.

Selecting Scene Setups

As you tour the location, look for setups that will visually help reinforce your story. If you’re shooting an interview with an expert, avoid cluttered desks and look for a place where they can stand near interesting lab backgrounds, devices with moving parts, or someplace where they can use their hands on the science gear they work with to lend authenticity to the scene. Though some scientists may express the urge to do the interview in their “comfort zone” of sitting behind their desks, reassure them that you’re job is to make them look and sound their very best. And your scene selection is an important part of accomplishing that. For instance, if it were one of our example manatee experts, we would have them standing, overlooking the water where they might see a manatee. That way they can look and gesture toward the water, which will be ideal points in the story to use your underwater footage of manatees. If it were an interview inside a building, we might have them stand in front of graphics or maps showing manatee locations.

When reviewing the potential scenes at a location, use your eyes as the lens of the camera. Look for settings with both interesting foregrounds and backgrounds. Bend over behind items and imagine your camera floating across the rows of foreground lab gear to the main work area where your expert is standing with more background devices and layers of lab stuff behind them. Also consider natural light sources, available electrical lighting, where you’ll set your lighting, backlighting, and how you might adjust your lighting to avoid talent or camera shadows. We’ll talk more about lighting your scene and talent in a moment.

Try to avoid scenes with excessive movement in the background such as road traffic or pedestrians. However, if your subject lends itself, such as the manatee example, it’s a bonus to have some background movement such as flying birds, wave action on the water, boats cruising past, fisherman, or whatever else may help tell your story. Also avoid setups with excessive horizontal and vertical lines such as fences, electrical lines, poles, and cabinets. Instead, look for scenes with diagonal lines that will add interesting and more dynamic perspectives to your shots. Sometimes, simply shifting the position of the camera can easily change those rigid horizontal and lines into more dynamic diagonal ones.

Take Charge of the Environment

Now that you’ve identified your main scene where you’re going to be shooting, it’s time to take charge of your shooting environment. One of the biggest challenges facing new producers and even some with considerable experience is fully taking charge of their shooting environment. If you think about it, you only have two options: letting the shooting environment take control of your production, or you taking control of your production by taking full control over your shooting environment… so that you can make things happen the way you want. Despite this advice, depending on where you’re shooting, your control of the shooting environment is a blend of being respectful to your location host and the logistics of what’s reasonable to expect.

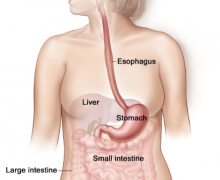

Here’s an example. If we’re shooting in a plant genetics lab and we don’t like the bright grow lights glaring down or the temperature control fans humming, we can’t simply turn them off and risk damaging the plant research. In most situations though, we can make the shoot more effective by taking charge and controlling various elements within the shooting environment. The rule of thumb is to change all that you can, and adapt what you can’t. Let’s break down those elements into bite-sized pieces so we can digest them one at a time.