Why do Athletes Train at Altitude?

Every time the Olympics come around we hear about the high altitude training programs of certain athletes. But what is it that happens to the body at altitude? To start this discussion we made a short video as we climbed the incline in Colorado Springs, the home of the Olympic Training Center.

Everyone seemed to know that high altitudes have less air, and many people then correlated that with the lack of oxygen, which is what we really need. Yet, I was surprised that most people think training at altitude seems to helps strengthen their lungs. While that misconception does seem to make sense, it simply isn’t the case. So let’s look at the science behind how our body responds to hypoxia (lower oxygen in the air).

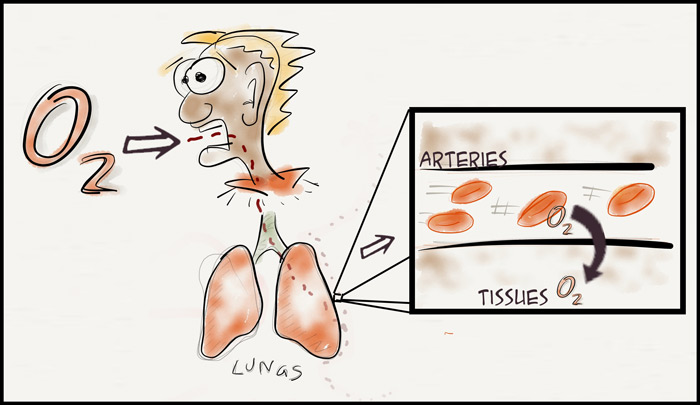

To start, we need to understand basically how we get oxygen to our tissues.

In the above diagram we see both the respiratory system and the circulatory system. The oxygen in the air is inhaled into our lungs. From there, the oxygen diffuses into our blood supply where it is picked up by red blood cells. Those red blood cells are pumped to our tissues such as the muscles we need during exercise. So again, the lungs are part of the system, but it turns out that altitude doesn’t really change the way our lungs work.

What does happen at altitude is multifaceted. Everyone will notice when they first get to altitude that they’re breathing harder when doing their normal exercises. They’ll also notice that their heart rate both when at rest and during exercise is much higher than normal. Both of these are needed to compensate for the decreased pressure of the oxygen (read as less oxygen available).

When you are at altitude your breathing rate does get higher though, so I can see where people are coming from. In fact, there are two ways to look at altitude – what happens to you in the short term and what happens in the long term.

Short term effects of altitude.

When people are exposed to high elevations where oxygen is limiting, there are certain things that happen.

- Increased resting and submaximal heart rates

- Increased blood pressure

- Hyperventilation

- Decreased plasma volume (the extra stuff in your blood that isn’t red blood cells or white blood cells)

- Increased reliance on glycolysis

- Decreased weight because of a lack of appetite and a shift in resources away from digestion

Long term effects of altitude

Even though the goal is acclimatization, there are still physiological differences in subjects that have long term exposure to higher altitudes. The following are seen in subjects that live at altitude.

- Increased HR at submaximal training (but resting HR is normalized)

- Increased blood pressure

- Hyperventilation

- Decreased plasma volume (meaning the blood is thicker)

- Increased hematocrit (meaning that there are more red blood cells in a drop of blood)

- Increased hemoglobin

- Increased capillarization in the muscle

- Increased mitochondrial density

- Increased myoglobin

- Increased reliance on glycolysis

- Decreased weight

- Body composition changes (usually meaning weight is decreased)

How long does it take to acclimate to altitude?

After studying the body’s response to altitude at multiple elevations, scientists have come up with a simple formula to figure out how long it takes the body to acclimate. Simply multiply 11.4 days per 1000m in elevation gain. Thus, if you’re at 3,000m (9,843 feet), it’ll take 11.4 x 3 or 34.2 days to fully acclimate to that elevation. This equation apparently works well up to 18,000 feet, but studies have yet to confirm if the trend levels out at the highest elevations.

How long does it take to deacclimate?

The unfortunate part for most athletes is that most of the positive effects of altitude are lost over time upon returning to lower elevations. The most talked about influence, an increase in red blood cells, is lost in about 15 days. Other adaptations however, like a change in how the body uses energy, stay with the body longer.

Are all athletes helped by altitude training?

Most people think that all athletes can benefit from altitude training, but that simply isn’t the case. You see, altitude training helps the body transport oxygen better, so it does seem to help endurance athletes, who are in aerobic competitions. However, if you’re doing anaerobic sports, like shot-put, dead lifting or sprinting, you just won’t get the benefits. In fact, because of the lower oxygen, it might actually hurt your training.

There is quite a bit of debate on this topic too. Even competitive endurance coaches suggest that altitude training isn’t necessary. The claim that time spent at altitude, where the body is struggling to adapt, actually takes valuable time away from effect training at lower elevations. Others claim that the best way to train is in low elevations, but sleep and live at high elevations (the so called Live High, Train Low program). For more on that see the following links.

Related Topics

Every time the Olympics come around we hear about the high altitude training programs of certain athletes. But what is it that happens to the body at altitude? To start this discussion we made a short video as we climbed the incline in Colorado Springs, the home of the Olympic Training Center.

Everyone seemed to know that high altitudes have less air, and many people then correlated that with the lack of oxygen, which is what we really need. Yet, I was surprised that most people think training at altitude seems to helps strengthen their lungs. While that misconception does seem to make sense, it simply isn’t the case. So let’s look at the science behind how our body responds to hypoxia (lower oxygen in the air).

To start, we need to understand basically how we get oxygen to our tissues.

In the above diagram we see both the respiratory system and the circulatory system. The oxygen in the air is inhaled into our lungs. From there, the oxygen diffuses into our blood supply where it is picked up by red blood cells. Those red blood cells are pumped to our tissues such as the muscles we need during exercise. So again, the lungs are part of the system, but it turns out that altitude doesn’t really change the way our lungs work.

What does happen at altitude is multifaceted. Everyone will notice when they first get to altitude that they’re breathing harder when doing their normal exercises. They’ll also notice that their heart rate both when at rest and during exercise is much higher than normal. Both of these are needed to compensate for the decreased pressure of the oxygen (read as less oxygen available).

When you are at altitude your breathing rate does get higher though, so I can see where people are coming from. In fact, there are two ways to look at altitude – what happens to you in the short term and what happens in the long term.

Short term effects of altitude.

When people are exposed to high elevations where oxygen is limiting, there are certain things that happen.

- Increased resting and submaximal heart rates

- Increased blood pressure

- Hyperventilation

- Decreased plasma volume (the extra stuff in your blood that isn’t red blood cells or white blood cells)

- Increased reliance on glycolysis

- Decreased weight because of a lack of appetite and a shift in resources away from digestion

Long term effects of altitude

Even though the goal is acclimatization, there are still physiological differences in subjects that have long term exposure to higher altitudes. The following are seen in subjects that live at altitude.

- Increased HR at submaximal training (but resting HR is normalized)

- Increased blood pressure

- Hyperventilation

- Decreased plasma volume (meaning the blood is thicker)

- Increased hematocrit (meaning that there are more red blood cells in a drop of blood)

- Increased hemoglobin

- Increased capillarization in the muscle

- Increased mitochondrial density

- Increased myoglobin

- Increased reliance on glycolysis

- Decreased weight

- Body composition changes (usually meaning weight is decreased)

How long does it take to acclimate to altitude?

After studying the body’s response to altitude at multiple elevations, scientists have come up with a simple formula to figure out how long it takes the body to acclimate. Simply multiply 11.4 days per 1000m in elevation gain. Thus, if you’re at 3,000m (9,843 feet), it’ll take 11.4 x 3 or 34.2 days to fully acclimate to that elevation. This equation apparently works well up to 18,000 feet, but studies have yet to confirm if the trend levels out at the highest elevations.

How long does it take to deacclimate?

The unfortunate part for most athletes is that most of the positive effects of altitude are lost over time upon returning to lower elevations. The most talked about influence, an increase in red blood cells, is lost in about 15 days. Other adaptations however, like a change in how the body uses energy, stay with the body longer.

Are all athletes helped by altitude training?

Most people think that all athletes can benefit from altitude training, but that simply isn’t the case. You see, altitude training helps the body transport oxygen better, so it does seem to help endurance athletes, who are in aerobic competitions. However, if you’re doing anaerobic sports, like shot-put, dead lifting or sprinting, you just won’t get the benefits. In fact, because of the lower oxygen, it might actually hurt your training.

There is quite a bit of debate on this topic too. Even competitive endurance coaches suggest that altitude training isn’t necessary. The claim that time spent at altitude, where the body is struggling to adapt, actually takes valuable time away from effect training at lower elevations. Others claim that the best way to train is in low elevations, but sleep and live at high elevations (the so called Live High, Train Low program). For more on that see the following links.