Is Natural History Really Dying?

Recently, I was doing research for a project at an entomology lab in Ecuador. I was researching behaviors of different groups of insects so that I could place them into certain “functional groups” (a grouping of organisms into some niche such as herbivore or predator). While doing so, I started to come across the same problem: there are so many things we do not know about so many of these invertebrates, especially regarding their behavior. Additionally, it seemed that most of the research I was citing was quite old now, and at first glance, there did not seem to be a lot of new natural history work being done.

During my training as an ecologist, I have briefly heard about a debate surrounding the decline of natural history—that natural history may be “dying”—and the idea that some do not consider it to be a true scientific practice. This, together with my inability to accurately complete my models from lack of behavioral information, got me thinking about natural history’s current place in science and ecology. To explore this issue, we must first understand what natural history is and how it is connected to everyday science and everyday life.

During my training as an ecologist, I have briefly heard about a debate surrounding the decline of natural history—that natural history may be “dying”—and the idea that some do not consider it to be a true scientific practice. This, together with my inability to accurately complete my models from lack of behavioral information, got me thinking about natural history’s current place in science and ecology. To explore this issue, we must first understand what natural history is and how it is connected to everyday science and everyday life.

Observing nature

There is something special about observing nature up close. As children, many of us spent hours watching various creatures in their natural habitat: bees buzzing in the flowers, ants carrying a seemingly impossible load across difficult terrain, a bird working tirelessly to feed a nest full of chicks. Many biologists share that these experiences are what made them pursue this career. Even for those who aren’t biologists, nature inspires something inside of us. Today, when it seems our connection to nature is threatened by growing cities and depletion of natural habitats, interest in nature continues to be important, whether through camping, visiting wildlife refuges, ecotourism, bird watching or watching varied and popular wildlife documentaries.

When we take the observation of nature one step further and begin to watch for patterns, describe interactions, identify what makes one species different from another, and record the world around us it’s called natural history.

A White-Whiskered Hermit (Phaethornis yaruqui) hovers near a flower of a Cepillo tree (Callistemon viminalis) in Quito, Ecuador Photo: Kirstynn Joseph

What is natural history?

Natural history is basically the study of flora and fauna in their environment, yet depending where you look, can be defined slightly differently:

A quick Google search will tell you that it is “the scientific study of animals or plants, especially as concerned with observation rather than experiment, and presented in popular rather than academic form.” The Merriam-Webster dictionary definition is: “the study of natural objects especially in the field from an amateur or popular point of view”.

Essentially, it is the close observation of the behaviors and interactions of organisms to help describe the patterns in nature. However, consider the words “popular” or even “amateur” in these definitions.

Natural history is considered the root of many disciplines of biology, especially ecology, and the basis of many important theories and discoveries, historically and recently. Despite this, there is sometimes a stigma that “natural history” is not a valid, modern science because scientists say it lacks careful experimentation and control of variables. A post from The Lyman Entomological Museum briefly discusses this debate and shows how important natural history is to modern science. However, what other evidence is there?

Is natural history science?

The difficulty with defining natural history as a science likely comes from the fact that you can have people who observe nature quite “amateurly” without using much of the scientific method; they may come up with conclusions based on observations alone, and that becomes complicated. Observations can also be biased, but with proper control and repetition they become very useful.

These observations, from scientists and amateurs alike, can develop theories or aid in conservation and management, as shown in this blog article and more research papers below. Many projects around the world are beginning to rely more on citizen science and observations, by using platforms such as eBird or iNaturalist or simply by communicating with people directly about their experiences, whether it is hunters and fishers from an area or local indigenous groups.

An ant (Ectatomma sp.) from Yasuni National Park, Ecuador. Photo: Santiago Palacios

In fact some wild interactions can only be deduced by making careful, repeated observations in nature; many organisms are difficult, if not impossible, to raise in a lab and some scenarios impossible to simulate. Even some small organisms like insects (many species of ants) are almost impossible to rear in a laboratory setting and must be observed directly in their habitat.

As an example, a recently published paper on the interactions between rhinos and oxpeckers showed that the birds’ warning calls help rhinos detect humans sooner. This was discovered through multiple field tests where rhinos were approached, with or without oxpeckers around, and their behavior was noted during each trial. This information is crucial to help with rhino conservation in regard to poachers; if we can help make sure oxpecker populations are doing well in rhino habitats, they may have a better chance at avoiding poachers.

This paper, Natural History’s Place in Science and Society, from 2014, noting the decrease in natural history over time, gives multiple examples of natural history being an important scientific practice in everything from ecology to human health and understanding disease. There are multiple published papers that also speak to natural history and citizen science as important tools for conservation and other research (some examples below).

These examples support natural history as a valuable and important science that can contribute to modern science. In saying so, is the practice, general interest in, and respectability of natural history in decline? Are we not spending enough time in the field observing our study systems? Is there a decline in natural history education? In short, is natural history dying?

What does the data say?

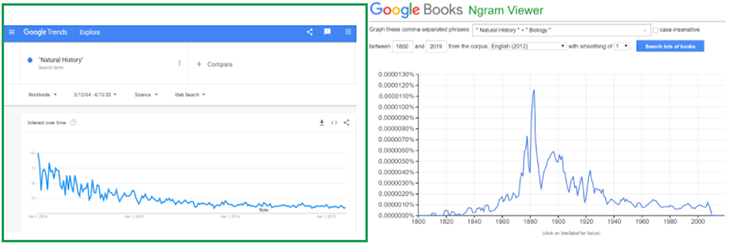

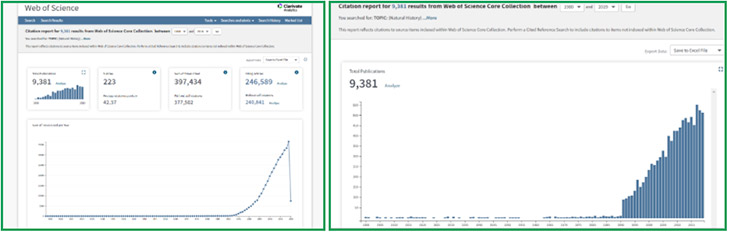

A quick look at Google Trends does show a decrease in searches of “Natural History” from the early 2000s through the present. While the Google Ngram Viewer shows that we are clearly past the peak of books published about natural history, titles have decreased since the 1930s, remaining somewhat steady after that.

On the other hand, the Web of Science citation analysis tool shows a clear increase in publications and citations with the topic “natural history” over time. Now, of course we must take into account that there likely has been a great increase in publications overall in this time, but surely this shows that natural history is not entirely dead?

These results suggest that natural history is not entirely in decline in terms of publications and books, but there are more opinions and lines of evidence to be explored. Let’s take a look at both sides of this debate.

Yes, natural history is dying!

In the late 1980s it was already known that natural history was underrated by the public and scientists alike but extremely important for conservation management and science in general (one example here). But where do we stand now?

Let’s start with schooling. As technology and science become more advanced, and statistics and modeling become more complex and important, it is widely argued that natural history classes are being pushed aside in order to train new biologists in theory rather than direct interaction with nature. This elimination from curriculums may be due to the stigma mentioned earlier.

As a new ecologist, I personally studied in a very different way than those from 20, 30 even 5 years ago. My university had a very strong statistical and theoretical curriculum (which I am very thankful for in many ways) but may have forfeited natural history study. I cannot say we never went to the field or learned interesting natural history facts, but I certainly spent much more time behind a screen than in the field.

As for graduate-level work, the immense pressure to finish your thesis, publish, and continue to be a competitive publisher, can edge out time for in-the-field study. Terry McGlynn argues this point quite well. In academia, this pressure doesn’t exactly lift after grad school, making it difficult to spend a lot of time on projects that require more time spent studying things more closely in situ. The stigma surrounding natural history as amateur science may also be a barrier to publishing in many journals.

Then there is funding. Funding tends to come more easily for projects focused on scientific trends, such as genetics, and as Google search showed, “natural history” isn’t exactly a burning topic.

Lastly, is there room in the workforce for natural history? There seems to be a drastic decrease in true jobs for naturalists and a worldwide decrease, removal, or consolidation of museums in different institutions. So, as much as you may love natural history, perhaps it is no longer seen as an employable field of study and the time spent outside observing interactions could be better spent at the computer learning the latest in coding for biological statistics.

No, natural history is not dying!

Like any argument there are two sides, and here we find a convincing argument that natural history is not threatened.

In many universities, there is surely a drop in courses that are strictly natural history, but perhaps we only have so much we can teach our students in an academic setting? As science progresses, may it not be more pressing to use classroom time to train these complicated math and modelling skills? Perhaps it is important to focus on learning how to navigate this new and important technology while trying to keep interest in natural history alive as the base of these projects, encouraging students to find other opportunities to get out and observe these systems when they can. Of course the ideal would be to offer and encourage natural history courses, or at the very least teach natural history skills, like identification, or facts about animal behavior throughout courses with heavy mathematical content, to remind students what we are studying and why.

Though there is a clear decline in these studies in some universities, many still offer animal behavior courses (e.g.zoology). There are also great university-sponsored programs that help students stay connected to natural history roots, learn how to conduct quality field work, and study nature, such as The Bamfield Marine Sciences Center in BC, Canada.

The issues of funding, publishing, and finding jobs are not exclusive to natural history but affect all scientists. So maybe the greater concern is to make science in general a priority in our society.

See also the large number of natural history museums worldwide, and that universities and institutions are investing in applications/webpages based on biodiversity and natural history. This certainly supports natural history’s relevance and popularity.

Furthermore, it is arguable that natural history can never be dead, because it is the foundation for ecology; to understand complex models properly you do need to understand the pieces of your study system and the behaviors and interactions within that system (see Fox and McGlynn). The complex models and statistics that are the landscape of modern science still rely on understanding nature and how it works, just through different approaches.

As seen in the graphs above, there are still publications and citations for natural history, and the numbers are even increasing. Each day there are fascinating papers and books released on the natural history of organisms, such as The Encyclopedia of Insects. Furthermore, though new technology is used in conservation work carried out across the world, it usually relies on a lot of direct observation and understanding the system first-hand or through communication with other groups as mentioned earlier.

While technology sometimes can be seen as the enemy, it also makes it easier to stay connected and share ideas, sightings, observations, and knowledge. Platforms like ebird, initiatives like The City Nature Challenge, and more are enabling and encouraging us to get out and see, enjoy, describe, and understand nature together. Additionally, wildlife filmmaking is becoming more widespread and popular and is an amazing way to share natural history between scientists and the public alike. All this information can be used to aid in public interest in nature and biology and in real scientific research. Perhaps, natural history is not only proving its relevance, but becoming a more well-rounded and useful tool than ever before.

Why should we care? Why is natural history important?

An iconic Galapagos Tortoise, one of the animals that helped Darwin with some of his first theories of evolution Photo: Kirstynn Joseph

Whether or not you think natural history is dead, dying, or as alive as ever, there is no denying that it is an important science that deserves recognition and our time. We are far from even describing how many species there are on Earth, let alone understanding their life histories and behavior, so we can hope that there is much more to come.

From getting students interested in nature, or reminding adults about its magic, to making important scientific discoveries, being a good ecologist, improving conservation practices, understanding ecosystem interactions, and advancing medicine and human health, natural history holds an important place in the scientific community. From the first observations of Darwin, that gave birth to the ecology we know today, or modern novel observations that lead to incredible discoveries about our natural world, to the light in children’s eyes as they learn for the first time how long a whale can hold its breath, or a biologist having that eureka moment while walking in the forest… natural history will always be a part of life. And it is so important that we do not forget that.

All the incredible science that is done every day helps advance the understanding of our big, complex, beautiful world, but we must not forget how important and helpful it can be to take the time to sit back, watch, and listen.

Sources / Further Reading

- Contributions to conservation outcomes by natural history museum-led citizen science: Examining evidence and next steps – Ballard et al 2017

- Is Natural History Still Relevant for Conservation Science? BY MATTHEW L. MILLER Nature.org 2014

- Natural History’s Place in Science and Society Tewksbury et al. 2014

- Natural History is Dying, and We Are All the Losers By Jennifer Frazer on June 20, 2014

- Stats vs. scouts, polls vs. pundits, and ecology vs. natural history Jeremy Fox Dynamic Ecology 2014

- Natural history is important, but not perceived as an academic job skill -Terry McGlynn Small Pond Science

- Systematics, Natural History, and Conservation: Field Biologists Must Fight a Public-Image Problem – June 1988 BioScience Jonathan B Losos Harry Greenery

- The importance of natural history studies for a better comprehension of animal-plant interaction networks – Bioscience Dl-Claro et al. 2013

- The importance of the natural sciences to conservation: (an American Society of Naturalists symposium paper).- Dayton PK 2003

- What is natural history anyway? September 29, 2012 -Terry Wheeler Lyman Entomological Museum

- Why Ecology Needs Natural History BY JOHN G. T. ANDERSON American Scientist

- Wildlife Biology and Natural History: Time for a Reunion – Steven G. Herman 2002

Some databases and websites for Natural History

The Untamed Science’s Tree of Life Project has a lot of great blogs and videos on The Natural History of a wide range of organisms, check us out!

You can go to The Naturalist Histories Project to see a range of discussions on the revitalization of Natural History. In addition, here are some great resources:

- Animal Diversity Web

- AntWeb

- AntWiki

- Bioweb Ecuador – this site is in Spanish but I have had the pleasure on contributing to this project and it is amazing and I wanted to share it

- eBird

- Encyclopedia of Life

- Fish Base

- GBIF -Global Biodiversity Information Facility

- iNaturalist

- Jelly Watch

- Map of Life

- The Natural Histories Project

- Tree of Life Web Project

- University of Florida’s Featured Creatures

- List of Natural HIstory Museums from Wikipedia -many of these museums have virtual databases

If I am missing some great websites, papers, articles, etc. please contact me on twitter and I will add them here!

Very interesting observation and I loved the video note from the author. Natural History should not die!