A crustacean packing a punch

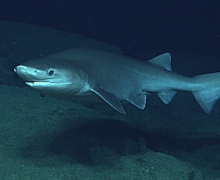

Don’t let the beautiful first appearance of these marine crustaceans fool you. Mantis shrimps (Stomatopoda) are not to be messed with!

Worldwide there are about 400 described species of Mantis shrimps. Even if they are fairly common in many tropical and sub-tropical waters, we still don’t know much about all of them as many spend much of their lives hiding in burrows and holes. But what we do know have earned them nicknames such as “prawn killers” (Australia) and “thumb splitters” (pretty much worldwide).

Mantis shrimps are commonly divided up into Spearers and Smashers. The names refer to the appearance of the first appendage or claw, which is used to catch prey.

Spearers have spiny appendages with barbed tips that look and work a lot like hand spears used in fishing. The spearing mantis shrimps rapidly unfold the appendages to catch and snag potential prey.

Smashers on the other hand have a slightly different and more developed method. The first appendages have large clubs strong enough to break the shells of snails and crabs. And if that wasn’t enough, they can hit with speeds of 23m/s and acceleration of more than 10,000 Gs, about the same acceleration as a .22 caliber bullet! It is the fastest punch in the animal kingdom, enough to break the glass of an aquarium, which they apparently have done! They are also known to protect themselves against any intruders or potential threats. Even humans who can’t keep their hands away. No wonder they are called thumb splitters…

This can leave one thinking how they can do this without breaking themselves? It turns out that the answer lies in both the chemical components of the club and how these components are packaged, giving the mantis shrimp an advantage against its hard-shelled opponents. It can therefore use the same club for thousands of hits before the club eventually needs to be replaced. Then animal then simply looses the old club and grows a new one.

The most well-known species of smashing mantis shrimps is the Peacock Mantis. In the saltwater aquarium trade, the peacock mantis shrimps are both loved for their beauty and hated for their violent personalities.

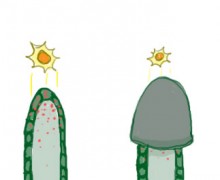

Eyes

Besides having the fastest punch, they also have the most complex eyes in the animal kingdom. They can see as many as 12 different colors (compared to human eyes that see three). In addition the mantis shrimp has four extra photoreceptor pigments for color filtering. In addition to seeing many more colors, the mantis shrimp can also see ultraviolet light and detect different planes of polarized light and circular polarized light. Plus their eyes are stalked, so they can turn them independently to scan pretty much everything around them without having to turn the body! So they can see what’s in front of them AND look at their own butt at the same time!