As you’ll discover, filmmaking is very much a creative endeavor, and one of the many beauties about the process is that there are no rigid guidelines. No two filmmakers will produce the same film about the same topic in exactly the same way. You are free to unleash your creativity and design any blend of elements to fulfill your filmmaking passion and to reach your audience. However, almost all filmmakers will agree that without following a clear plan, you and your film might come across as a jumbled mess of ideas.

If you want the film to impact your audience, you will need a plan designed for that audience and a clear vision of how you are going to show and tell your story. When you tell an audience what to think by presenting a series of facts and evidence, you may fail to engage them and inhibit them to think for themselves. However, if you show your audience a sequence of images accompanied by graphics and a catchy soundtrack, but leave out the facts, you run the risk of losing your message altogether. A carefully planned design can both show and tell your film’s story. Your plan should blend creative genius with a practical approach to effectively reach your audience.

To demonstrate how you can achieve the type of film that will show and tell your message, let’s walk through a typical pre-production meeting at Untamed Science.

Start by laying some groundwork. Ask the following foundational questions of any filmmaking adventure:

- What are the goals of the film?

- Who is the target audience?

- What is the story?

- What is the take-home message?

- What distribution methods will we use?

- What are the production roles?

Your plan doesn’t have to be an elaborate document; an outline works fine. However, the more details you include up front, the more clearly you define the vision of your production.

Choosing a Topic and Defining Your Goals

First, define the goals of your film. This will help make you aware of the information that you need to gather and the pertinent facts you need to tell your audience. Make a list or, better yet, have your production team brainstorm together. Once you have a list, pare it down to three or four complementary (and realistic) goals. Here are some examples:

for a Wildlife or Natural History Documentary

- Make the audience aware of a species in peril.

- Make them care enough about the species to take action.

- Identify causes that harm the species.

- Inspire social change to end harmful causes.

for a Science Film

- Connect a science topic with a problem in the audience’s lives.

- Reveal how science offers solutions.

- Explore how the audience can become part of solution.

- Change the audience’s stereotype or perception of the topic.

Your goals may be something that you come up with or something that a client brings you. One of our clients, for example, simply wanted to save the Florida manatees. Your job as a filmmaker is plan a film that will do that most effectively. But who are you making the film for?

Identify Your Target Audience

Your target audience is the group of people you want to watch your film. It can be as broad as the general population or as specific as the members of the Denver Geophysical Society. Knowing your target audience will help you plan the key elements of the story and relevant production techniques.

Armed with our defined goal to save the manatees, we would brainstorm with our production team to identify the potential audience. In this case, our audience might include:

- Florida boating and fishing associations

- Drainage commissions and engineers

- Florida travel and tourism

- Florida fish and wildlife officials

- Coastal residents near manatee habitats

- Nature and outdoor associations

- Students in the area

Though we ideally want the entire country to know about and help save the manatees, our target audience should be people who are impacted by our story and who have the most influence to help save them. Perhaps we concentrate our efforts on Floridians in the age range of 16 to 29, a group that may not even notice the plight of the manatee until we bring it to their attention. Next we would define our story, gather information, ask our “big questions,” and produce our “take-home message.”

Defining Your Story

Next we outline the elements we might want in our story. Jot down whatever comes to mind, but try to think from the perspective of your target audience. Then arrange your ideas as key questions in an order that would create a logical development for a film, for example:

- What’s a manatee, and why are they unique?

- What’s happening with manatees today?

- What things are threatening them?

- Who is responsible for harming them? For helping them?

- What experts or personalities can offer quality content?

- What can be done to save them?

- How can the viewer get involved?

This list establishes a clear direction for our film. We can elaborate or refine each question as we gather the materials to answer them. The logical and progressive development of your questions helps refine your grand plan and increases your chances of a successful production.

Develop the Big Question and Take-home Message

To keep our film on track and give it focus, we need to refine “the big question.” What’s the singular most important question that the film should answer for the audience? A logical choice from our example list could be, “What things are threatening [the manatees]?” Identifying the big question helps keep you focused during planning and production. It might be easy to get lost in the excitement of shooting your underwater segments with the manatees or interviewing some Hollywood personality dedicated to saving them, but if you remain true to answering your big question, it will help you keep focus.

Also, by presenting the big question early in your film, it frames the theme for your audience. You might have heard that to answer a question thoroughly, you have to ask several more questions. For instance, asking “What things are threatening them?” will lead you to ask how a manatee survives in the wild, what type of environment they live in, or how they adapt to living in a habitat affected by human intervention. The questions may become more specific: are pollution, changes to their natural ecosystem, or biological deficiencies threatening the manatee? Asking and answering these types of questions will develop a logical flow for your film. The answers also may help lead your audience to make their own conclusions.

Developing the big question can also help your audience anticipate the possible solutions. By summarizing all the facts presented by experts and science content within your film, you empower your audience and give them a sense of ownership in answering the big question for themselves.

You should also develop a clear “take-home message.” From our list, the take-home message might be answering the question, “What can be done to save [the manatees]?” The answer might inspire them to do something about the dilemma portrayed in the film. For example:

- People have the power and resources to save the manatees.

- Government and organizations need to join forces to save the manatees.

- You can help save them with these five simple steps.

From these messages, select the one that is most realistic, concise, and that best matches the biggest segment of your target audience. Now you are ready to consider how your production style can best connect with your audience.

Style

This is also the time to decide on the slant, presentation style, point of view (POV), and feel of your film. In short, you need to determine how you’re going to tell your story. Will the story be narrated, host-driven, expert-driven, or a combination of these? Will the feel be edgy where the camera and POV feel like they are part of the unfolding action or discovery? Or, will it have the more classic feel of a “blue-chip” documentary (such as Planet Earth or Blue Planet)? Establishing how the story will be told early on will help the production team preserve the feel of your film throughout the entire production process—from planning, to shooting, to editing. In our manatee example, we might decide to have an edgy, investigative, documentary style, realistically unfolding the facts to compel the younger audience we have chosen.

Define Length and Methods of Distribution

Though you’re a long way off from distributing your film, identifying exactly how your target audience will view it is an important part of your early plans. It will help you design the style, length, and presentation of your film. For example, if we want to air our manatee film on television or at film festivals, we might consider a 20- to 30-minute format. That gives us a number of options on developing the depth of our content and determines how much information we can present. On the other hand, if we choose to distribute it on a DVD or at formal meetings (to organizations we listed as other possible audiences), we might have the luxury of producing a feature-length production (more than 40 minutes). If we want to make a music video on saving the manatees that we want to go viral on YouTube, then we may want a three-minute format where we dive headlong into the message with fast-paced action and quick cuts between short segments.

Untamed Science has produced hundreds of science education videos that are intended to inspire students in classroom settings. From this experience, we have learned that a five- to six-minute production works most effectively for classroom delivery. Four minutes is not quite enough time to add all the elements to engage, entertain, and inspire a student; and longer videos seem to test attention spans.

Define Production Roles

The final part of your plan is to list the key roles in the production process and consider who might be the most qualified in your production team to assume those roles. You might be talented enough to perform all the roles in making a film: planning, scripting, directing, shooting, hosting, editing, special effects in post-production. But it’s a huge job for a single person! It’s a good idea to spread the filmmaking workload across the ranks of your recruited talent.

Here are the key roles in making a film:

1. Producer

The producer’s job is to assemble the entire crew. Producers are the team-makers. They don’t have to be on location, write the script, or edit anything if they find the right crew. However, in most small documentary productions, the producer is often the scriptwriter and director.

2. Scriptwriter

Scriptwriters may write a treatment (a detailed first draft usually written like a short story) of the film content to present to funding agencies. After funding is approved, the scriptwriter crafts a more detailed outline or script. This gives the director, hosts and camera crew something to reference while making the film.

3. Researcher

A researcher’s role is to do the background checking on a topic to present the best focus for a film’s content. For example, they might find the best sources for supporting our manatee film, list the possible experts, get the facts together, and make sure those elements can actually be shot. They often work with the scriptwriter to check facts and aid the logistics coordinator’s job. Recent graduates with biology degrees often make great researchers.

4. Logistics Coordinator

The logistics person should arrange all of the physical concerns for the busy film crew. They make travel arrangements, contact experts, get location or facility permits, and generally ensure that everything at the location is ready for the shoot.

5. Cameraperson

Good camera operators are worth every penny. They should be able take your shot list and capture everything to show your story through the lens of the camera. Most documentary camerapersons are skilled with lighting setups and may bring a light kit to a shoot. They are responsible for working with the location director and sound person.

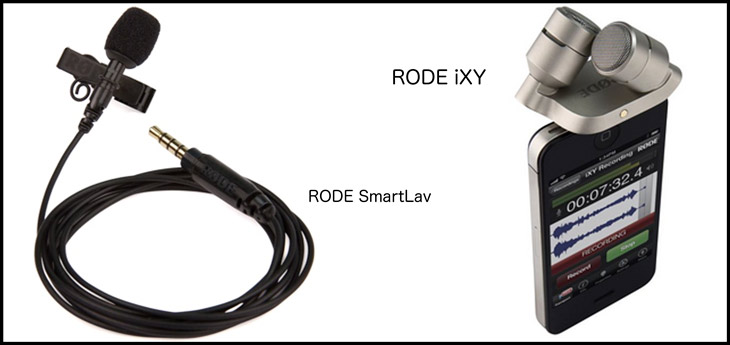

6. Sound person

While a skilled cameraperson may also serve as the sound person, most documentaries with a decent budget will have an assigned sound person that knows their stuff. Having poor quality sound can ruin a segment. The sound person will generally carry a mixer and keep all incoming audio sources separated and at the proper levels before they feed the audio signal into the camera.

7. Location Director

The location director is in charge of envisioning and directing each segment. The director will guide the cameraperson and think one step ahead of them. For instance, directors will interview the experts while the cameraperson is getting the shot lined up. In addition, while the cameraperson is shooting manatees in the water, the director may direct the talent to quickly get in the shot and give a quick account of what’s happening. A camera person can only do so much with their eye on the viewfinder, so a director who can think ahead and envision footage before it happens is key to a great shoot.

8. Host

If the style calls for it, the host has a huge role as the main character of the film. His or her voice and actions tell the story. This might mean just having fun. While that sounds easy, it can be difficult to block out the stresses of a production and get into a fun mindset. The host should know the material backward and forward so they can give impromptu responses to the camera. The host should memorize any scripts the production requires. Hosts are the representative face and voice of the film and should take special care with their physical appearance and costumes.

9. Narrator

A professional narrator in a studio should work with the director to produce a quality narrative voice that fits the feel of the film. Professional narrators often have their own studio and can deliver narrative audio online. Also consider the advantages of working in-person with local narrators. Working in person can help to direct the right pacing and inflection in telling the narrative story.

10. Editor

The editor may or may not have been behind the camera or at the shoot location. On site, they will see what story elements were captured through the lens and can quickly assemble the essence of the story in the editing timeline. For some productions, though, editors need to tell the story objectively from the collected footage and not rely on the story as it appeared to the film crew. An editor who was not involved with the shooting may have a more open mind and only create an objective story with the footage that exists. Regardless, the editor should review the footage then work with the director to come up with the compelling story. The editor may also work with animators to come up with graphics that support the production.

11. Animator

Animators are brought in for sections of a production that may need compelling 2D or 3D graphics to tell a portion of the story. Most animators are hired as sub-contractors and work under the direction of the director or editor.

12. Distributor

Distributors are often well-connected within the industry and can be brought in after a production. Ideally, it’s better to work with a distributor before the completion of the film to develop a distribution plan that will build an audience for your film. Despite the potentially helpful role of a distributor, you ultimately have the most at stake in the successful distribution your film, so take an active role in planning the distribution.

Of course, you could probably come up with many other rolls in a production. Where are the grips, PAs, executive producers, musicians, stunt coordinators and the casting directors? Compared to the credits listed in a typical Hollywood film, our list of roles is pretty sparse. Nonetheless, it represents the major roles you will need to fill with talent. How you fill those roles with talented people depends on your budget, and the talent and interest of your friends, classmates, relatives, and fellow filmmakers. Let’s assume that you’re limited on budget and prospective talent pool, and you’ll need to combine some roles. We often combine roles on smaller productions. But make sure to avoid assigning people with roles that may overlap, such as camera person and host. Here are some logical combinations:

- Producer, scriptwriter, director, sound person

- Cameraperson, editor, animator

- Host, narrator, researcher, logistics assistant

In this example, you may only have three people on your crew, but that can be enough to produce your film. To take full advantage of your small crew, be sure to exchange ideas openly and help one another during each phase of production. For instance, the director, host, and cameraperson can all help dress the set or prep the location, work with lighting and audio while collectively offering ideas on how to best shoot a segment. Having the camera person as the editor gives that person the advantage of knowing what shots to get during shooting for the upcoming edit. Later on, the editor will already know the shot inventory that he or she filmed as the camera person. It can make for an effective overlap of roles.

Where to get talented crew?

Chances are that you have already gained some industry contacts that will help you assemble your production crew. If not, and if you will be hiring professionals, you should network with other local production companies for recommendations. If you are unsure about using a person to fill a role on your crew, ask for their demo reels or samples of their work. Hire the most talented crew members you can afford. Saving a few dollars on a cameraperson or editor with limited experience or talent could jeopardize your entire production. On the other hand, if you are on a small budget, you might get creative in building your crew.

Getting a Low-budget Crew

What if your friends, classmates, or relatives don’t have the required talent or interest in filmmaking? You may need to search out and recruit “low-budget” talent for your film. First, let’s make the job easier by further combining roles. If this is your film, you should be able to assume all of the roles except the host and possibly narrator. If you are a good host, you may need to recruit only a cameraperson. (An animator might be one other role you may need to recruit; it depends heavily on the content of your film. Some science topics, such as chemistry, need to be revealed at the molecular level that can’t be captured by the average video camera, so a good animator can make those concepts come alive for the audience. If the topic demands it, add an animator to your recruitment list.)

If you can’t afford to pay talent with hefty fees, consider paying them with a nominal payment for services, end-credit notoriety, experience in filmmaking, services traded (they help you and you help them), product or gear trade, or a creative combination of these.

But where do you find that potential host, cameraperson, and animator? Fortunately, they are often in similar places. Here’s a list of where to begin your talent search:

- Community college or technical institutes that offer courses in your science topic, filmmaking, media, or acting

- College graduate programs that cover your science topic, filmmaking, media, acting

- Local television news stations

- Local filmmaking or production groups

- Local theater productions or acting schools

It is pretty amazing what you can accomplish in your search by using the Internet. Craigslist, batch emails, or casting calls can turn up dozens of leads in no time. And don’t forget the timeless telephone cold call. Even if your prospective sources can’t help, many of them will have other names and contacts they will pass along if you ask.

One final note about looking for narrators: if you don’t have a quality host and need to put narrative flair into your film, take the extra time to find a narrator that fits the theme and feel of your film. Online searches will give you dozens to choose from and many of these sources will allow you to listen to samples of their voices. Just be sure their talent fee matches your budget.